Changing the history course

When Sam Wineburg joined the faculty of Stanford Graduate School of Education (GSE) in 2002, he knew he wanted to pursue a different approach to the way K-12 schools teach history. Instead of having students memorize names and facts from a textbook, why not equip them to investigate the evidence for themselves, just as historians do?

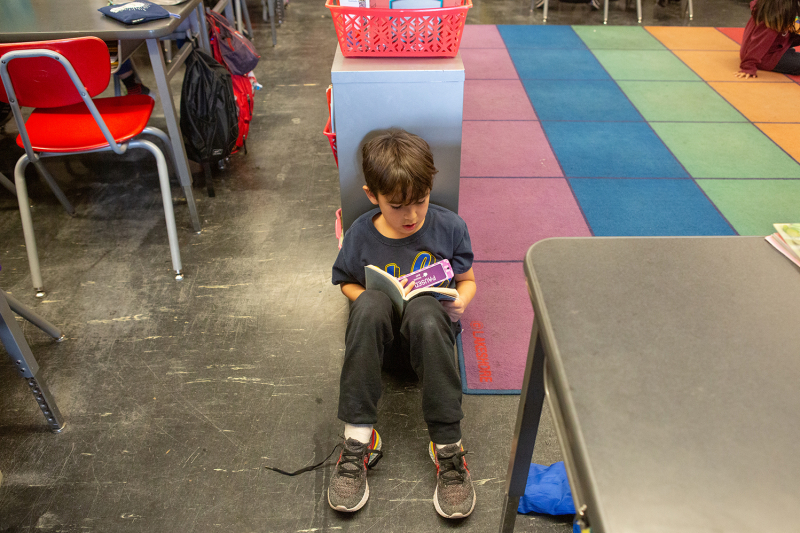

His own research had shown that with the appropriate guidance, even fifth and sixth graders could work with documents like diaries, speeches, and works of art to explore questions about the past. And as the world’s mode of delivering information was becoming increasingly digital, he knew that teaching students how to scrutinize sources would be critical beyond the history classroom — they were skills for becoming informed citizens in a democratic society.

His groundbreaking approach became the premise of the Stanford History Education Group (SHEG), an organization that has become renowned for its innovative, research-based approach to teaching history and, more recently, digital literacy. Over the past two decades, the group has created a rich repository of lessons for different grade levels, all freely available on its website, and partnered with school districts around the world to help educators use the materials in their classroom.

To date, SHEG’s resources have been downloaded more than 16 million times by educators from all 50 states and from countries around the world. Forty-one state departments of education in the United States include its materials on recommended lists. UNESCO bestowed the organization with an award for its work communicating best practices in media literacy in 2020, and a California law that went into effect last month requiring media literacy instruction in schools cited SHEG’s research in its rationale for the legislation.

Now SHEG is moving into a new era as the Digital Inquiry Group (DIG), an independent nonprofit that launched this month.

“Our main objective has always been to create materials for the classroom that are easy to use and go beyond the single voice of the textbook,” said Wineburg, the Margaret Jacks Professor Emeritus of Education at Stanford, who founded both SHEG and its new incarnation, DIG. “We’ve made a few bets, trying to figure out where we’d have the most influence with limited resources. But with all of our research and all of the resources we’ve developed, it’s always been about empowering students to make sense of the past and the present.”

Incubating a new approach at Stanford

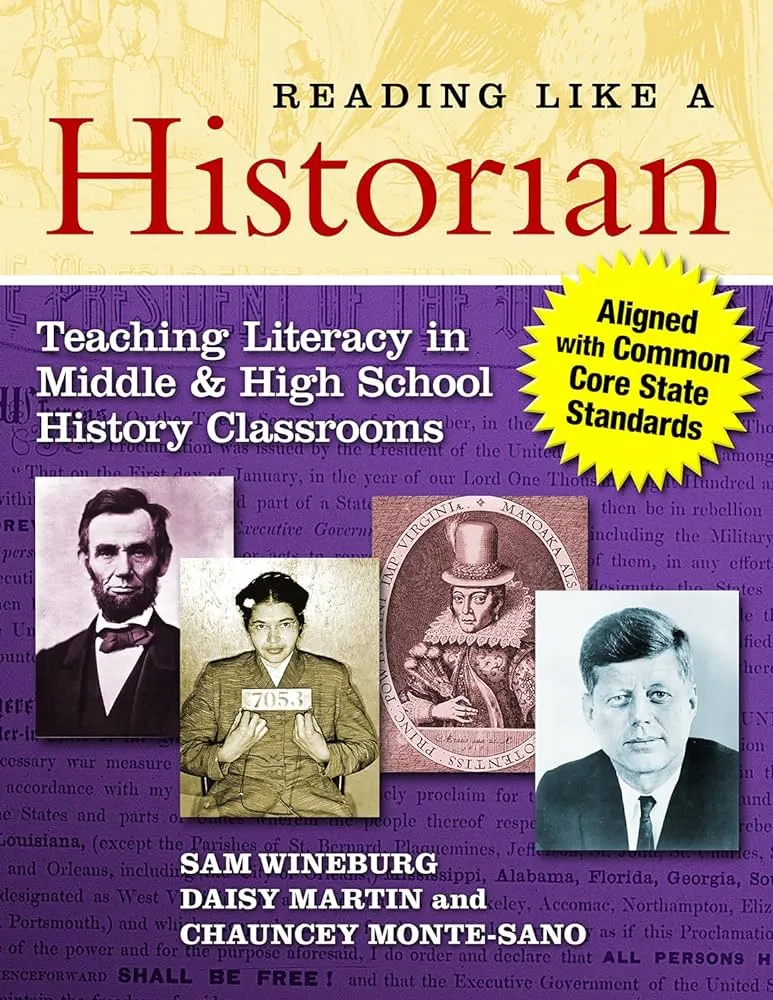

The book Reading Like a Historian, published shortly after the authors developed the curriculum, shows how to apply the approach to middle and high school classrooms.

Back in 2002, before there was a SHEG, Wineburg launched his approach in a course for prospective high school teachers in the Stanford Teacher Education Program (STEP).

“STEP was really a laboratory for developing these new teaching methods,” said Wineburg, who piloted curriculum materials he developed with his first two teaching assistants, Chauncey Monte-Sano, PhD ’06, and Daisy Martin, PhD ’06. (Monte-Sano is now a professor of education at the University of Michigan, and Martin directs the History & Civics Project at the University of California at Santa Cruz.)

The document-based curriculum his team created, called Reading Like a Historian, introduced students to historical thinking, a set of skills historians use to analyze and understand historical events in context. Using primary sources designed to be accessible at different grade levels, students investigate questions about history: Did enslaved people build the Great Pyramid at Giza? Why did U.S. senators oppose joining the League of Nations in 1919? Was Social Security revolutionary, or a program designed to appease Americans who wanted more profound change?

The first major test of the curriculum came in 2008, when Abby Reisman, PhD ’11 (now an associate professor at the University of Pennsylvania), led a large-scale study with the San Francisco Unified School District (SFUSD).

Students in the test classes showed not only an increased ability to retain historical knowledge and a greater appreciation for history, but also improvements in reading comprehension and critical thinking.

This twofold finding reflects the curriculum’s ability to bridge skills that K-12 history teachers sometimes view in conflict, said Rob McEntarffer, supervisor of assessment and evaluation for Lincoln Public Schools in Nebraska, a district that has participated in SHEG research over the years and integrated its resources into the curriculum.

“There’s long been a pendulum swinging back and forth between an emphasis on content knowledge versus critical thinking skills,” McEntarffer said. “Some teachers identify as content experts and emphasize historical content in their classroom, and others think that students are going to forget all the content, so they want to emphasize 21st-century thinking skills. But SHEG’s research [showed] that it’s a false dichotomy.”

After the SFUSD trial, at the district’s request, Wineburg and his team built a website to house the investigational curriculum. “We called ourselves the Stanford History Education Group and posted our materials online,” said Wineburg. “And to our tremendous surprise, we realized that people were downloading them from all over the country.”

Joel Breakstone (center) leads a group of social studies teachers in discussion during a professional development workshop on materials developed by the Stanford History Education Group, now the Digital Inquiry Group. (Photo: DosEckes Productions)

A ‘clear picture of need’

The curriculum provided just the kind of lessons that Joel Breakstone, then a high school history teacher in rural Vermont, had long sought.

As a history major at Brown University, he’d been taught to work with first-hand accounts of historical events, and he wanted his students to do the same. “But as a high school teacher I found that really challenging,” he said. “Primary documents aren’t written at a grade level that’s appropriate for 15-year-olds, and giving William Lloyd Garrison speeches to students at 7:37 in the morning doesn’t go very well.”

He found SHEG’s materials online and, inspired to explore the methods further, he enrolled in a doctoral program at the GSE, earning his PhD in 2013 and then taking on the role of SHEG’s director.

He was soon joined on staff by fellow alum Mark Smith, PhD ’14, who as director of assessment helped expand the team’s resources with Beyond the Bubble, tools using documents from the Library of Congress’ digital archive to help teachers track students’ progress with the curriculum.

In 2016, after conducting a high-profile study of how students from middle school through college struggled to evaluate the reliability of information on the internet, the organization expanded its work into Civic Online Reasoning, a curriculum focused on ways to detect misinformation based on research observing professional fact-checkers at the nation’s most prestigious news outlets. Wineburg conducted this research with GSE graduate student Sarah McGrew, PhD ’19, now an assistant professor at the University of Maryland.

“Our research painted a very clear picture of need, and we realized we had to develop a better approach to supporting students in becoming discerning consumers of information,” said Breakstone, who served as executive director of SHEG for the past ten years and continues in that role with the Digital Inquiry Group. “Even though our name was the Stanford History Education Group, we were working more generally to help students understand where information comes from and how to consider the source.”

Far-reaching impact

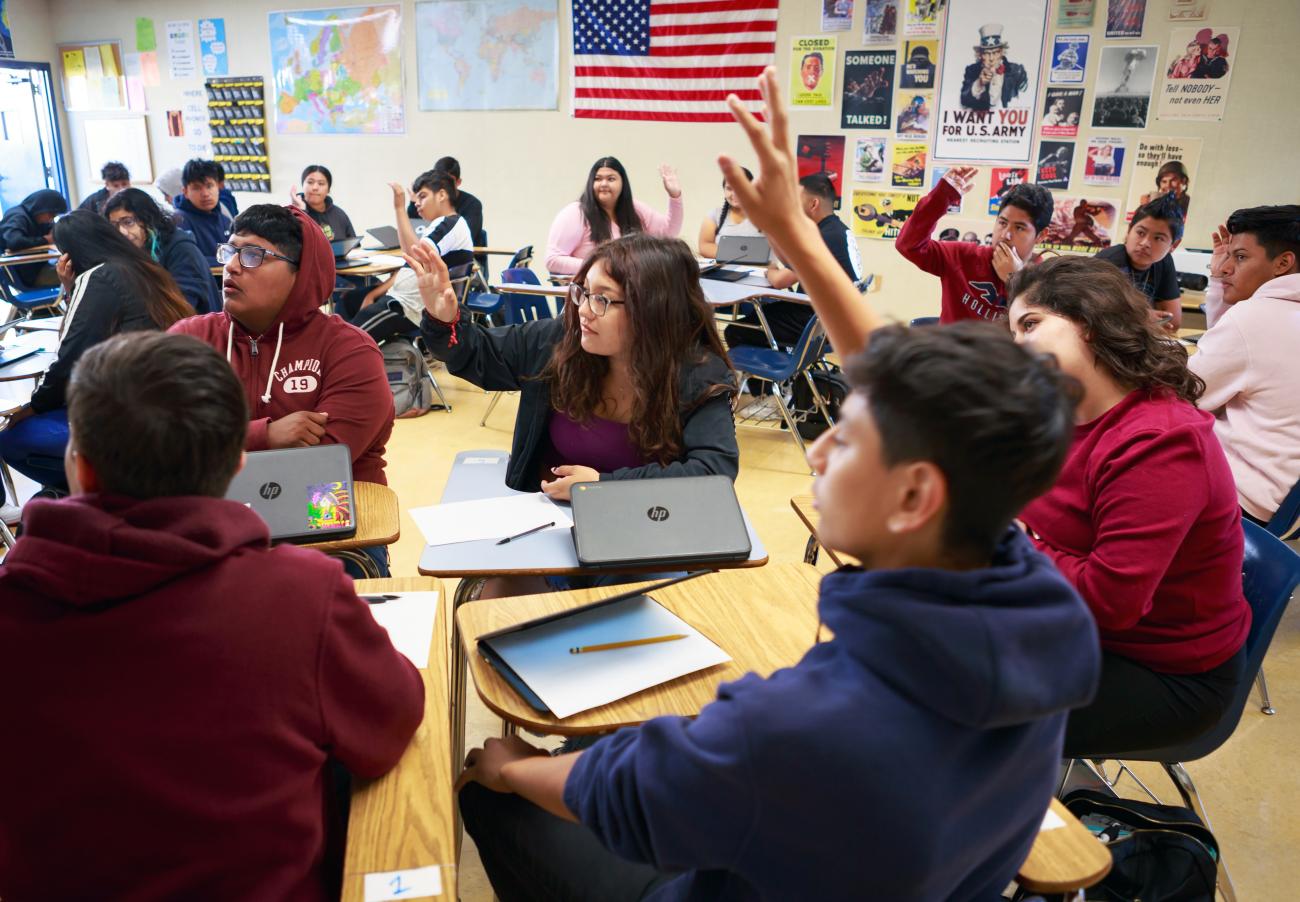

The team consults with school districts of all sizes to help educators use its materials, including a decade-long partnership with the Los Angeles Unified School District (LAUSD), the second-largest district in the country. SHEG has led numerous trainings every year for LAUSD since the district adopted the Reading Like a Historian curriculum in 2014.

“These trainings are one of the most requested, and they fill up immediately,” said Kieley Jackson, history and social science administrator at LAUSD, who estimates that about 1,500 teachers and 250 administrators in the district have now been through the training. “I’ve had veteran teachers quite frankly confess to me that they were in stages of burnout, and SHEG’s professional development sessions reignited the spark.”

Even with a curriculum focused largely on American history, SHEG found fans around the globe. In Australia, Jonathon Dallimore, executive officer of the History Teachers’ Association of New South Wales, praised the organization for showing a generation of teachers that it’s possible to use primary sources with young learners — for providing a model, and showing that it works.

“The great power of the material is that it’s an introduction into some really complicated ways of thinking about the world,” he said. “These are incredibly mature concepts about time and perspective and the way people operate, which hopefully can help students develop confidence and humility at the same time.”

Beginning its new chapter as an independent nonprofit, the group plans to expand its offerings, from additional professional development opportunities (including “on demand” workshops) to new tools to help schools integrate digital literacy into core subjects across the curriculum.

Through a licensing agreement with Stanford, all of SHEG’s materials will remain freely available on the DIG website.

“As a small group, we’ve always sought to make as much noise as possible,” said Breakstone. “It’s been remarkable to see the reach we’ve had, with a staff of no more than four people at a time — seeing folks in California and Arkansas, Italy and Sweden, Columbia and Taiwan, all taking up these ways of doing history and digital literacy. As DIG, we hope to have an even greater impact.”

Faculty mentioned in this article: Sam Wineburg