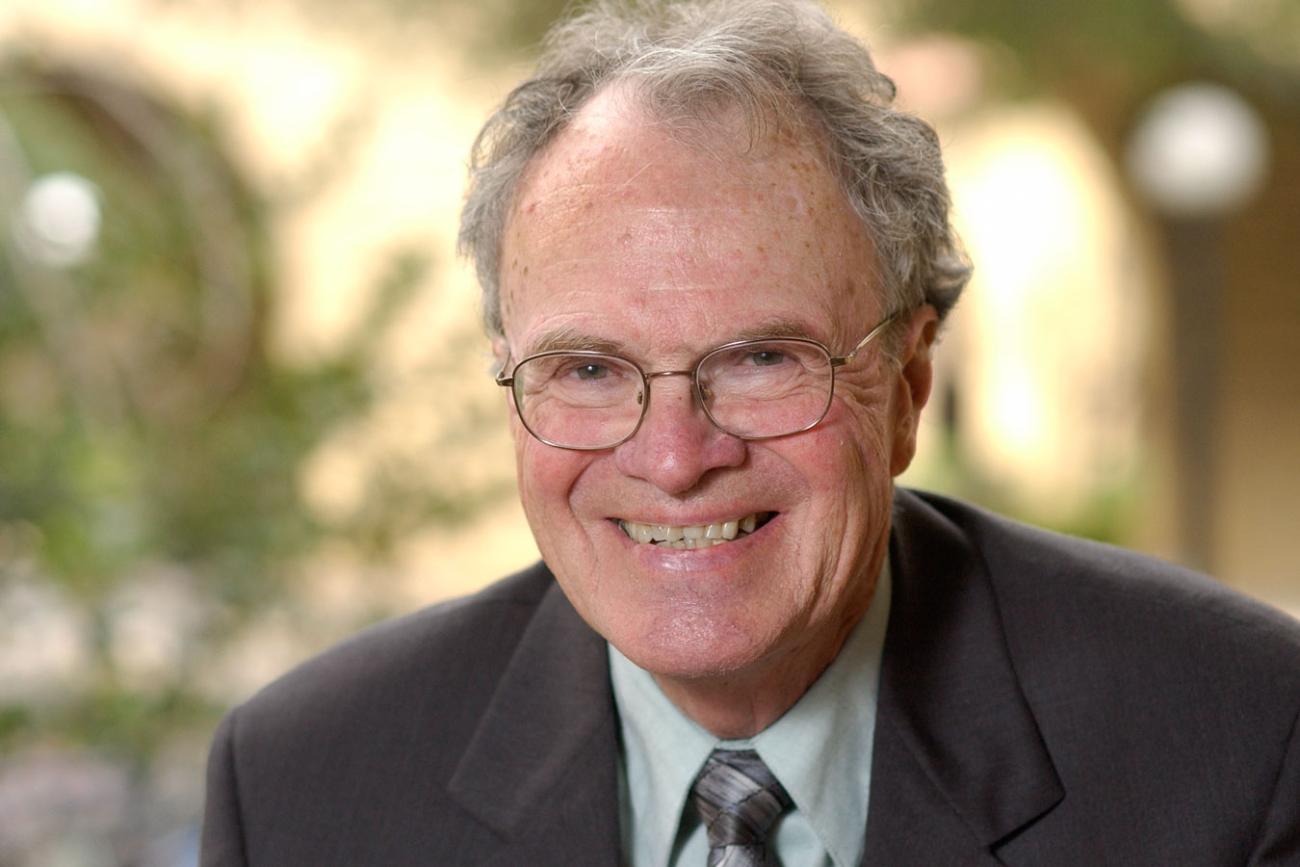

Stanford Professor John D. Krumboltz, who developed the theory of planned happenstance, dies

John D. Krumboltz, retired professor of education and of psychology at Stanford, died May 4, 2019, at his home on the university’s campus. He was 90.

Krumboltz, who came to Stanford in 1961, revolutionized the fields of behavioral and career counseling by applying social theories of learning to the making of life decisions.

In his six decades as one of America’s most influential psychologists, he was co-director of the Stanford Graduate School of Education’s program in counseling psychology and the widely read author of many scholarly and popular books, most recently Fail Fast, Fail Often: How Losing Can Help You Win (with Ryan Babineaux, PhD ’04, 2014).

By demonstrating the value of counseling in a social context, Krumboltz inspired advances ranging from multicultural counseling to behavioral health care treatment.

“He was one of the first researchers in the field to place outcomes before process and to use scientific methods to determine whether certain psychological interventions worked,” said Teresa LaFromboise, Stanford professor of education.

“Especially among psychologists, he was the rare instance of someone who seamlessly stitched theory with practice,” said Kenji Hakuta, Lee L. Jacks Professor of Education, Emeritus. “He was a great teacher with an incredible diversity of students who admired and emulated his modeling. He also was a sympathetic and empathetic listener.”

Throughout Krumboltz’s sphere of influence, LaFromboise observed what she called “an air of veneration for his ability to treat people with enduring kindness.”

His honors include the American Psychological Association’s 2002 Award for Distinguished Professional Contributions to Knowledge and its 1990 Leona Tyler Award for advances in counseling psychology.

Other books he authored or co-authored include Behavioral Counseling: Cases and Techniques (with Carl E. Thoresen, 1969); Changing Children’s Behavior (with Helen B. Krumboltz, 1972) and Luck is No Accident: Making the Most of Happenstance in Your Life and Career (with Al Levin, 2004).

Retiring in 2015, Krumboltz remained active on campus, mailing copies of his books from his GSE office and writing a personal dedication in each.

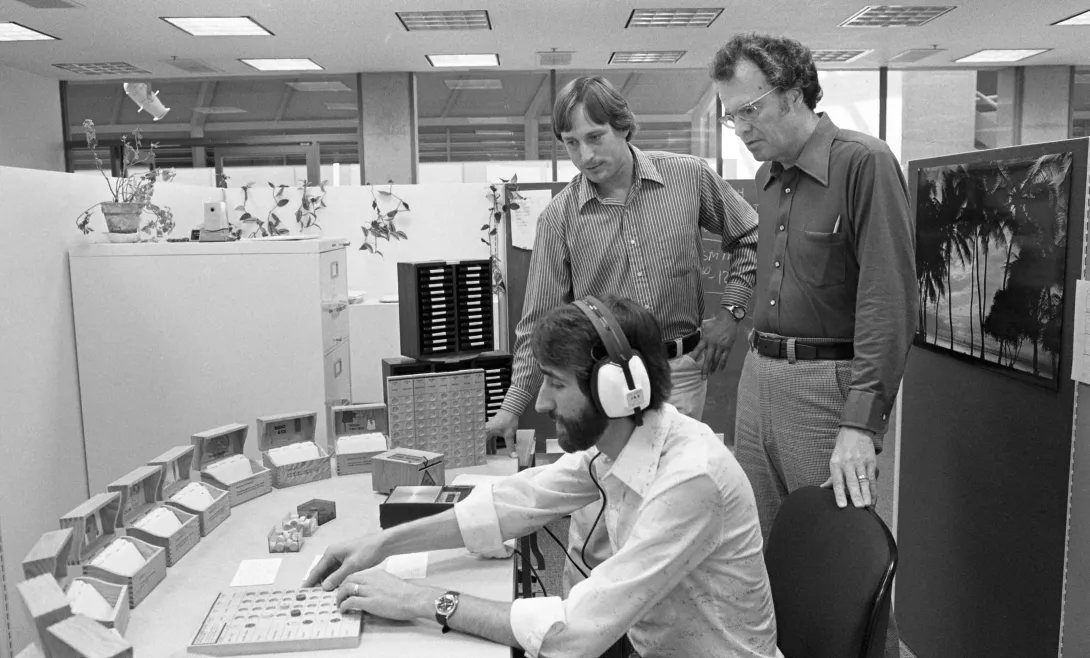

John Krumboltz, right, with a simulation game for choosing careers. (Image credit: Jose Mercado)

Planned happenstance

Krumboltz was born Oct. 21, 1928 in Cedar Rapids, Iowa. He completed his undergraduate work at nearby Coe College, where he played varsity tennis and where he was prompted to study psychology by his coach, who also taught the subject. Krumboltz learned tennis, he said, only because he once rode a bicycle down an unfamiliar street where he saw kids playing a game that looked like fun.

He often cited this experience when talking about planned happenstance, the theory he developed with Levin and Kathleen Mitchell that says arbitrary events have important influence on people’s lives.

“You can’t say, ‘I’m going to teach you to ride a bicycle so you will major in psychology,’” Krumboltz said in 2013. “All these events that happen in life are unpredictable – and let’s be grateful that they’re unpredictable.”

In addition to planned happenstance, Krumboltz’s key scholarly work at Stanford included pioneering research that verified the effects of behavioral counseling interventions on client behavior. He developed the social learning theory of career decision making and the construction and validation of the Career Beliefs Inventory.

“What I most admired was that John didn’t always follow customary theory and proposed unconventional counseling strategies,” said one of his first students, H.B. Gelatt, EdD ’64.

In co-leading the Counseling Psychology program with Professors Carl Thoresen and LaFromboise, Krumboltz said the first goal in its mission statement was for students to “develop a personally satisfying and balanced life.”

Krumboltz earned his master’s degree in counseling at Teachers College, Columbia University, and his PhD at the University of Minnesota. He was senior research scientist at the U.S. Air Force’s Personnel and Training Research Center at Lackland Air Force Base in Texas, then taught educational psychology at Michigan State University.

He was recruited to Stanford by education Professor H.B. McDaniel, himself a guidance-counseling pioneer.

In tribute, Krumboltz would later help to found the H.B. McDaniel Foundation, which supports educational counseling through awards, student grants and annual conferences at Stanford.

Among his many activities, including a regular tennis game with colleagues on campus, Krumboltz supervised the student-led Stanford Institute for Behavioral Counseling on Alvarado Row, which served the surrounding community.

In the early 1970s, Krumboltz successfully argued against reinstating “F” grades at Stanford, which had been abolished in 1969.

“Making a permanent public record of failed attempts at mastery discourages academic exploration, instills a fear of learning, and impairs attainment of the purposes for which Stanford was founded,” he wrote in Campus Report in 1992.

He abhorred reliance on testing to decide individuals’ fates, writing in 1981 that counselors cannot “prescribe a single occupational pill that will produce future euphoria.”

Rather, he said, they should teach people to ask, “What would be fun to try next?”

Krumboltz also believed that school counselors should not be limited to emotional problems or career guidance, which put them “on the fringe of the educational endeavor,” he wrote in 1987. Counselors should encourage students to love learning by integrating the insights of teachers, parents and others.

Krumboltz is survived by his wife, Betty; a brother, David; a sister, Margaret Ann Phillips. His blended family includes daughters Ann Krumboltz, Jennifer Krumboltz Somerville and Shauna Foster Nance and her two sons, Nicholas and Joshua; a son, Scott D. Foster; and four nieces and two nephews.

Memorial services are pending. The family asks that any memorial donations be directed to the H.B. McDaniel Foundation in Kingsburg, Calif.