Stanford initiative reveals racial, gender, other disparities in Brazilian schools

Earlier this year, when the Brazilian government reported its official data on the number of K-12 students nationwide with disabilities or learning disorders, Stanford education scholar Guilherme Lichand thought the figure seemed off.

According to data from Brazil’s annual school census, less than 4 percent of K-12 students have some type of physical or learning disability. But Lichand expected the actual number would be much higher, given U.S. rates and the international average.

Lichand, an assistant professor at Stanford Graduate School of Education (GSE) who is originally from Brazil, runs an initiative called Equidade.info (Portuguese for equity), which collects data on K-12 schools in Brazil through interviews with students, teachers, and administrators across the country.

Spurred by the dubious census figures, the team recently investigated the prevalence of physical and learning disabilities in the country's K-12 schools – arriving at a rate of at least 12.8 percent, more than three times the official statistic.

“There are differences in socioeconomic backgrounds that make it less likely for some kids to get a medical diagnosis,” said Lichand, who also co-directs the Stanford Lemann Center, a center housed at the GSE that supports Brazilian scholars at Stanford and initiatives to improve the Brazilian educational system. “But the government data is what determines how school resources are allocated. If you’re a policymaker making decisions based on incomplete data, kids are not necessarily going to get the support they need.”

Equidade.info, a project of the Stanford Lemann Center, analyzes data from a representative sample of schools throughout Brazil on a variety of issues, from chronic absenteeism and reading proficiency to racial relations and students’ sense of belonging.

GSE Assistant Professor Guilherme Lichand

Some of the initiative’s findings so far:

- About a quarter of K-12 students report being a victim of bullying during the previous 12 months. Females report higher rates than their male peers, and non-white students report higher rates than white respondents.

- Students’ sense of feeling welcome at school decreases as they progress from elementary to high school, with Black students reporting lower rates overall than their white classmates.

- The prevalence of child labor among the student population is eight times what official statistics indicate.

- Internet speed in schools is much lower than official data indicates, with a significant disparity between public and private schools.

- More than half of teachers report witnessing cases of racial discrimination in schools – data cited in a recent push by Brazilian legislators urging the Ministry of Education to address racism in the country’s educational system.

In the country’s annual school census, information on many key markers of inequality is absent or incomplete, said Lichand, who is also a faculty affiliate of the Stanford Center on Early Childhood and the Stanford King Center on Global Development, and a fellow at Stanford Impact Labs and the Stanford Institute for Advancing Just Societies.

“Without precise information about differences along dimensions like race, gender, and disability status, education policies often magnify inequalities instead of alleviating them,” he said. “We need better data to design more equitable policies. So we established a different system for collecting it.”

Marta Vitória, an enumerator for the state of Sergipe, conducts a survey with a student for Equidade.info.

What the school census doesn’t capture

In Brazil, most of the Ministry of Education’s information on the state of K-12 schools comes from the annual school census, which solicits information on all 49 million students at 160,000 schools nationwide. Census responses are supplied by school staff, ideally but not necessarily drawn from information provided by students and their families.

“The only way you can get that much student-level data is to sacrifice quality in the way that you collect the data,” said Lichand. “One can only hope that what the schools are providing about these 49 million students is accurate.”

Given the lack of oversight for the process, Lichand questions the reliability of the data, especially where factors like race and disability status are concerned. These are complicated constructs by any measure, he said, particularly if the designation isn’t self-reported but determined by a school official or other figure.

With race, for example, Lichand said Equidade.info has found a discrepancy for 30 percent of students between what they report their race to be and what the school reports. Schools also have the option of not reporting students’ race in the first place, an option that’s prevalent in the data, Lichand noted.

“Until 2014, there was no information on race for half of the students in the country,” he said. “More recently, the government has made efforts to have schools provide this information, but still at least a quarter of students are missing race data.”

Lichand’s data collection model for Equidade.info goes deeper than the school census with in-person surveys of a representative sample of more than 200 schools from all of Brazil’s 27 states. The sample reflects key characteristics of the school population nationwide – urban and rural schools, public and private, technical and academic – serving students of all backgrounds, including indigenous populations. The researchers use statistical methods to ensure the results mirror the universe of K-12 students, teachers, and schools.

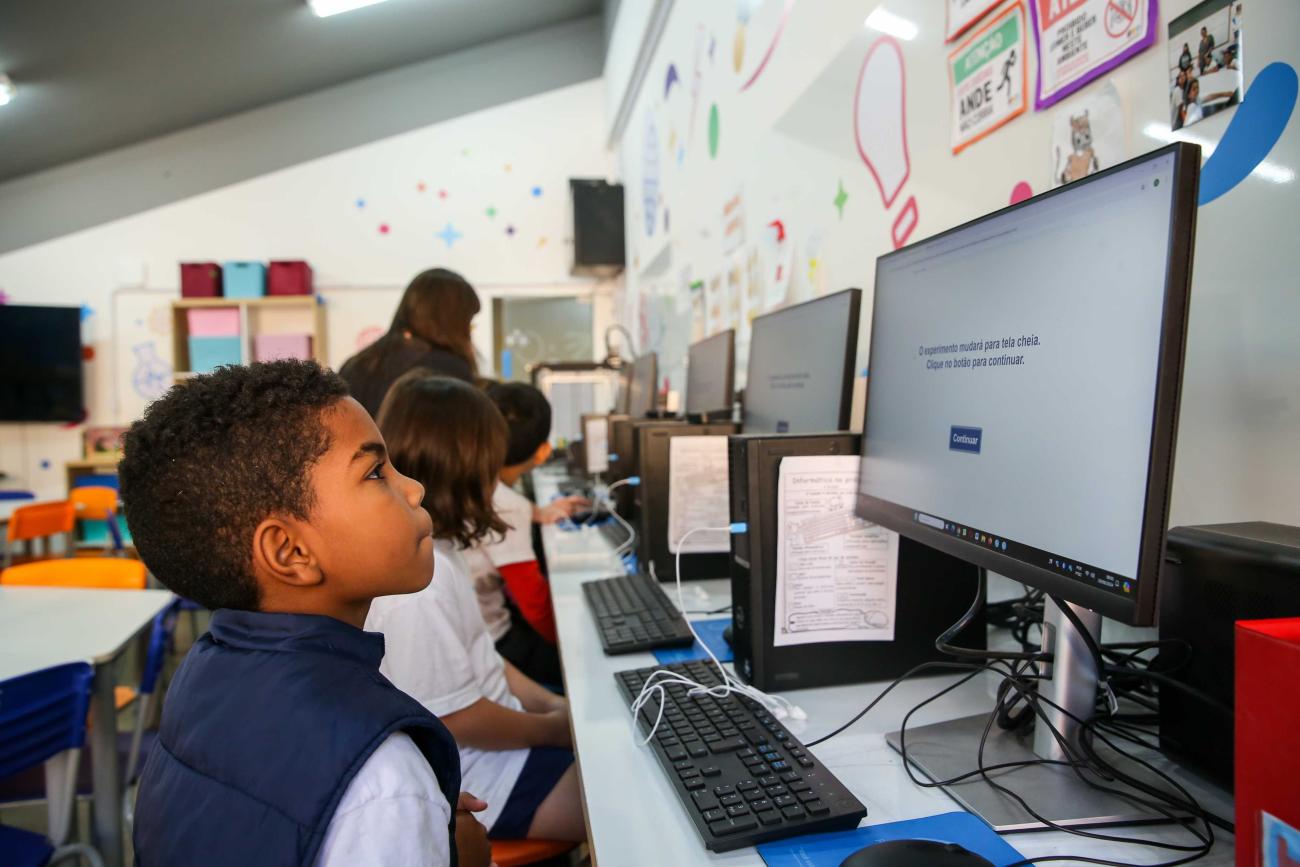

College undergraduates in each state are recruited and trained to serve as enumerators, visiting local K-12 schools every two months to conduct tablet-based surveys or run tests.

“Our enumerators can collect data that the school census doesn’t capture,” Lichand said. “They can ask students to self-identify their race. They can have students do tasks that indicate certain abilities, like reading fluency and comprehension. They can measure the school’s internet speed objectively, by connecting to the wifi network and running a speed test app.”

Because the enumerators visit the schools every two months, the surveys can include questions related to issues of the moment, like a mass school shooting or the wildfires currently raging in Brazil. “We can ask principals how many days of school they’ve lost to climate events, what kind of adaptation measures they have in place,” said Lichand. “We can be really responsive to what’s going on, and generate timely data that’s useful for policy and the public debate.”

The initiative’s website provides dashboards to visualize key insights from the data, particularly around gender, racial, and regional disparities, and all of the information is shared with the Ministry of Education.

Timely feedback on learning differences

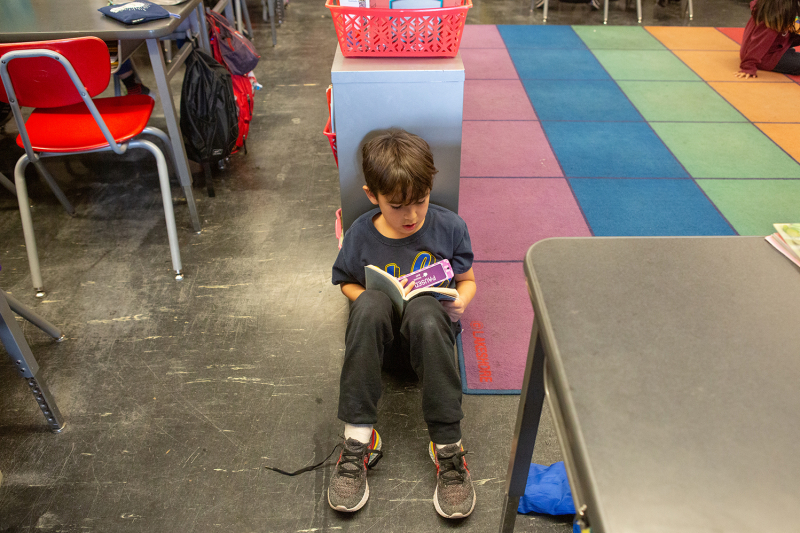

Lichand is also working with other GSE researchers to adapt new U.S. digital reading and math assessments for use in Brazil, not only to support research but also to provide teachers with timely, personalized feedback on learning differences so they can more quickly support students who fall behind.

A Nov. 8 conference at the GSE will explore the potential of using the two Stanford-developed technologies in Brazil: the Rapid Online Assessment of Reading (ROAR), led by Associate Professor Jason Yeatman, and the Stanford Mental Arithmetic Response Time Evaluation (SMARTE), led by Professor Bruce McCandliss.

Lichand, an educational economist and entrepreneur, hopes to replicate the model he created for Brazil with Equidade.info for other low- and middle-income countries in the Global South, especially in Latin America and Africa.

“We know that high-quality data is in demand,” said Lichand, who is frequently featured in Brazilian media discussing Equidade.info’s findings. “As researchers, the nature of our work is to put knowledge out there and hope that it makes its way to change policy. Now we are starting to work closely with officials to be sure we can meet their specific data needs, creating pathways to support equitable policies.”

Júllia Kessia (in forefront), an enumerator for the state of Alagoas, poses for a photo with a group of young students she surveyed for Equidade.info.

Faculty mentioned in this article: Guilherme Lichand