Stanford undergrads join local high school students and their teachers for an uncommon learning experience

Students at Sequoia High School in Redwood City, Calif., are joining Stanford undergrads in an uncommon learning experience from the Stanford course catalog: an ethnic studies class that brings students and teachers from both campuses together to learn from each other.

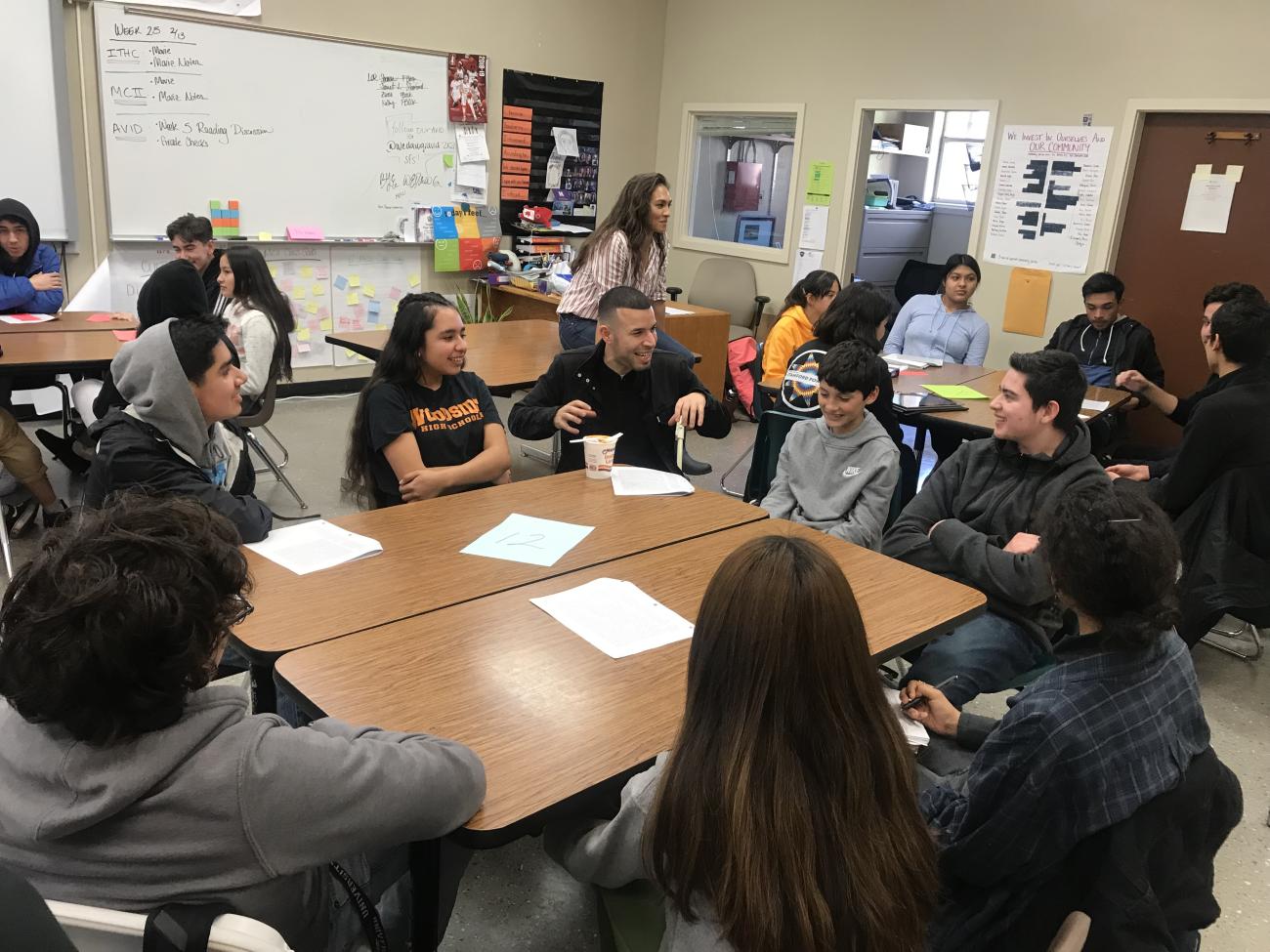

The course – Introduction to Latinx Studies, led by Stanford Associate Professor Jonathan Rosa – stands out for its unusual approach. Co-facilitated by five teachers from the high school, the course fully integrates the Stanford and Sequoia participants’ experience, building a world of knowledge that goes beyond the boundaries of campus.

“For me, recognizing and understanding and sharing knowledge from outside of the university is absolutely central to the vision of ethnic studies,” said Rosa, an associate professor at Stanford Graduate School of Education (GSE) and the Center for Comparative Studies in Race and Ethnicity. “I didn’t feel comfortable teaching this course without a community engagement component.”

An evolving partnership

The course grew from a longtime collaboration between Stanford GSE, Sequoia High School and the Haas Center for Public Service. Rosa, who also directs the Chicanx/Latinx Studies program at Stanford, joined the faculty in 2015 and soon began working with Sequoia and the Haas Center to adapt his introductory course into a community-based experience.

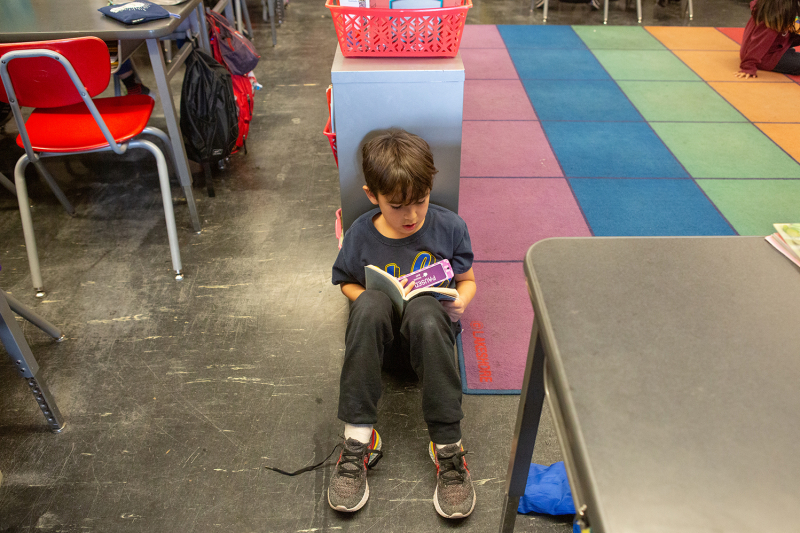

Before the pandemic, some 20 to 40 Stanford undergrads would travel to the high school in Redwood City each week, attending Rosa’s class with Sequoia sophomores who took the course as part of an academic support program that prepares students for college eligibility and success.

This year, for the first time, all Sequoia students in grades 9-12 were invited to apply. Thirty were selected to join 25 Stanford undergrads in the course, which was held online during the pandemic.

A new grant from the Haas Center this year also made it possible for several Sequoia high school teachers to take on a substantial role in facilitating the course – turning it into a learning experience for the educators as well, as Sequoia prepares to launch its own ethnic studies curriculum for ninth graders this fall.

“I wanted this to be a true collaboration,” said Rosa. “I’m not teaching this course ‘for’ the Sequoia students or staff. The teachers and I are co-facilitating, and the Stanford students are just learning this material as much as the Sequoia students are. We’re all learning and teaching together, and that’s central to this experience.”

“For me, recognizing and understanding and sharing knowledge from outside of the university is absolutely central to the vision of ethnic studies,” said GSE Associate Professor Jonathan Rosa. “I didn’t feel comfortable teaching this course without a community engagement component.” (Photo: Toni Bird)

Building knowledge as a collective

The reciprocal learning environment in the classroom sets Rosa’s course apart from many community partnerships at Stanford and elsewhere, said Paitra Houts, MA ’08, director of community engaged learning in education at the Haas Center.

“Often when we talk about community-engaged learning, we think about courses where students are tutoring or doing a project for an organization,” she said. “In Jonathan’s class, everybody in that space is learning something new from each other, building knowledge as a collective.”

The class explores issues including the history and legacy of European colonization, Chicanx/Latinx literary and cultural traditions, assimilation and identity, and political and economic shifts. Discussions draw not only from Rosa’s lectures and a rigorous reading list but heavily from the students’ lived experience.

“In privileged spaces, there are all kinds of knowledge that we’re not sensitive to – knowledge about labor, about migration, about survival, about citizenship,” said Rosa. “These are forms of knowledge that exist in families and communities. The university is not the only place where we hold and create knowledge. The university is where we give order to knowledge, where we reproduce it and typologize it in certain ways. But knowledge is created everywhere.”

That premise set the tone for a course that dissolved traditional hierarchies.

“I thought I would be one of the grown college students mentoring the high schoolers, teaching them things about Latinadad,” said Kevin Calderon, a senior at Stanford majoring in comparative studies of race and ethnicity. “But the class was structured for all of us to learn together, for us to see ourselves and the high school students as people situated in different knowledge bases.”

A million miles away

About 60 percent of students at Sequoia High School identify as Chicanx/Latinx, said Elisa Niño-Sears, a program director at the high school who has collaborated with Rosa on the course from the start.

“Sequoia is 20 minutes from the Stanford campus, but it can feel like a million miles away,” said Niño-Sears, a 1995 Stanford alum. Before the pandemic, when classes took place at the high school, she observed a shift in the Stanford students – the majority of whom also identify as Chicanx/Latinx – after they entered the building.

“You could see them kind of become their old selves,” she said. “I think being in a more normal place was reinvigorating for a lot of the Stanford students, who can get into the mindset that if you don’t have your app and your venture capital funding by the time you’re 20, life is over.”

Photo of Sequoia High School courtesy of Wikimedia Commons

For the high schoolers, taking a course alongside college undergrads might have been daunting. But many described their reassurance at finding a supportive community and developing trust in the older students over time.

“In the beginning of the course, I could tell that some of us were shy and a little scared to put our opinions out there, because these were Stanford kids and they seemed really smart,” said Daniella Acosta Lopez, a rising senior at Sequoia. “But we warmed up throughout the course. I realized there was no reason for me to be shy. It was a judgment-free zone.”

“I was super nervous, but honestly, it turned out to be like any other group work,” said Haylee Huynh, who begins her sophomore year at Sequoia this fall. “I didn’t feel a power dynamic between the college students and the high school students, and I was one of the youngest of the high school students.”

An unconventional apprenticeship

Rosa began learning how to structure and implement this type of course while he was an assistant professor at the University of Massachusetts at Amherst, where he found a mentor in Ginetta Candelario, a sociologist at Smith College and ardent proponent of community-based learning.

“I approached her and asked, ‘Would you be willing to talk with me about how you do this?’ And she said, ‘If you want to learn, you can’t just talk about it. You have to do it. Come and be a student in my course.’ ”

Rosa took her up on it. “I was a tenure-track faculty member, and I took her course. I took myself seriously as a learner and went every week.” That sense of humility, the rejection of hierarchical norms, is essential to community-engaged learning, Rosa said. “I had to humble myself as a learner in order to do this work, too.”

Once at Stanford, Rosa tapped into existing relationships and resources to advance his vision. The Haas Center has provided ongoing funding and hands-on support, including a community-engaged learning coordinator, a Stanford undergrad employed to support faculty with Cardinal Courses.

“There are a lot of logistical moving parts, and that student is absolutely essential to this project,” said Rosa.

This year, in addition to funding Stanford undergraduate Angela Gomez in that role, the Haas Center provided Rosa with additional support through an Advancing Racial Justice in Teaching grant, one of several offered in 2020-21. “We wanted a lot of that funding to go to our community partners as honoraria,” Houts said, “to compensate them for work that is often not recognized.” Rosa directed the funds to the Sequoia teachers for co-facilitating, making the course more of a shared project than it has been in the past.

Students described a supportive community among the high schoolers and Stanford undergrads (pictured together here before the pandemic).

‘It was just how I wanted to teach’

For the Sequoia teachers, the course served an additional purpose this year as they worked to develop materials for a new ninth-grade ethnic studies curriculum launching at the school this fall.

“This was exactly what I was looking for, the content and the strategy,” said Diana Nguyen, a 2018 graduate of the Stanford Teacher Education Program (STEP) and one of the Sequoia teachers who co-facilitated the course this year. “It was just how I wanted to teach but didn’t have the words to explain.”

The Sequoia students, meanwhile, found role models of their own in the Stanford crew. In Rosa, for one, they saw “that being intellectual doesn’t mean being condescending, that being academic doesn’t mean being removed in some tower or in the back of a library,” Niño-Sears said. “It’s incredible for our kids to see a Latinx male professor they can relate to. He knows about the musicians who are coming out now. He’s sharing about getting boba tea. He’s sharing about his haircut. They get it, that they could be like him.”

Sharing all kinds of experiences, from the mundane to deeply formative, transformed a group of students and teachers with perceived rank and status into a true community of learners, all contributing their own knowledge and questions.

“So much of learning is about storytelling, coming together and having conversations,” said Melissa Díaz, a Sequoia history teacher and 2019 STEP graduate who also co-facilitated the course. “This experience really showed me that, with strong supports and scaffolds in place, anyone can be in a class together and learn from each other.”

Learn more about ongoing collaborations between Stanford Graduate School of Education and community partners, including local school districts.

Faculty mentioned in this article: Jonathan Rosa