New Stanford research lab explores incarcerated students’ educational paths

From her earliest jobs – first as a camp counselor, then as a daycare worker and school teacher – Subini Annamma always liked working with the so-called “difficult” kids.

“I didn’t find them difficult,” said Annamma. “I thought they were funny and interesting, really engaging. They were just kids.”

As a special education teacher in middle and high schools in Oregon, California and Colorado, she started noticing that some of her students would disappear for stretches of time – to juvenile incarceration facilities, it turned out. In part for more insight into their trajectories, she decided to “follow” them and began teaching in youth residential treatment centers and prisons.

Annamma, now an associate professor at Stanford Graduate School of Education (GSE), continues to pursue a deeper understanding of the relationship between special education and youth incarceration. Examining the policies and practices that have led to students of color being disproportionately represented in both settings, she explores what education does – and could – look like in a place designed largely for punishment.

This year, with Stanford Law School (SLS) Professor Ralph Richard Banks, director of the Stanford Center for Racial Justice, Annamma launched the Walkout! Lab for Youth Justice, part of an initiative by the Stanford Center for Comparative Studies in Race & Ethnicity to establish racial equity action labs at Stanford.

The Walkout! Lab is part of a deepening relationship between the GSE and the law school. Annamma and Banks first collaborated in 2020, teaching a course together (with Professor Bill Koski, PhD ‘03; SLS alum Tara Ford; SLS associate dean and lecturer Diane Chin; and the pro bono law firm Public Counsel) to explore what it would take to create an antiracist public education system.

Annamma and Banks teamed up again to create the Walkout! Lab, combining Banks’ expertise in legal and policy analysis with Annamma’s in the criminalization of multiply marginalized youth in education.

The Walkout! Lab is distinct among other youth justice research projects for its focus on education, Annamma said. “When people look at youth prisons, it’s often from a criminal justice lens,” she said. “Rarely do we look at the education that goes on inside these spaces.”

Associate Professor Subini Annamma

A tradition of activism

The name of the lab reflects a long tradition of student activism that Annamma and Banks wanted to honor and emphasize, a tool that young people have used for generations to push for change in society and education.

“Walkouts are some of the most powerful organizing tools students have in schools,” Annamma said. “Sometimes when youth decide to stand up for themselves, adults will downplay it and say they’re being manipulated by other people. But if you’ve ever worked with students, you know they’re often very certain about the choices they’re making.” (The exclamation point in the name, she said, is a symbol of that certainty.)

In staffing the lab, Annamma included three formerly incarcerated young Black women she’d met through an earlier research project. In individual projects done through the lab, she will consult formerly incarcerated youth from across the country.

“My first questions to them are: What do you want people to understand about youth prisons? What do you want them to know about the time you spent there?” Annamma said. “It was really important to make their voices central to the aims of this lab. They’re sharing the kinds of questions they want answered, and they’re going to learn research skills and how to do data collection and analysis, along with policy change.”

Graduate students and faculty from Stanford and other universities will also bring their expertise to the lab as fellows. “The work has to be interdisciplinary,” said Annamma. “It has to cross geographical and generational spaces. There is no solving these problems without multiple kinds of expertise and backgrounds.”

Uncovering identities and experience

The Walkout! Lab recently launched a two-year project, funded through a grant from the Ford Foundation, aimed at better understanding the population in youth incarceration and how education policies and practices influenced their paths. (Annamma uses the term incarceration to refer to any location youth are sent to after being removed from their homes, including juvenile detention and residential treatment centers.)

“Kids, especially the ones who have been pushed to the margins, are in the best position to tell us what works and what doesn’t. In all of my work, I want their voices to be at the center.”

Subini Annamma, Associate Professor, Stanford Graduate School of Education

For Annamma – whose work explores the experience of multiply marginalized students, particularly youth of color with disabilities – one thing that stymies her research is a lack of information about the multiple identities of students who are incarcerated.

“In California, for example, the state collects data about race and we collect data about gender, but we don’t collect data on disability or LGBTQ status,” Annamma said. “From small studies, we can guess that we have a lot of Black and Brown kids with disabilities and Black and Brown kids who are queer and gender nonconforming in youth incarceration. But we can’t actually show that.”

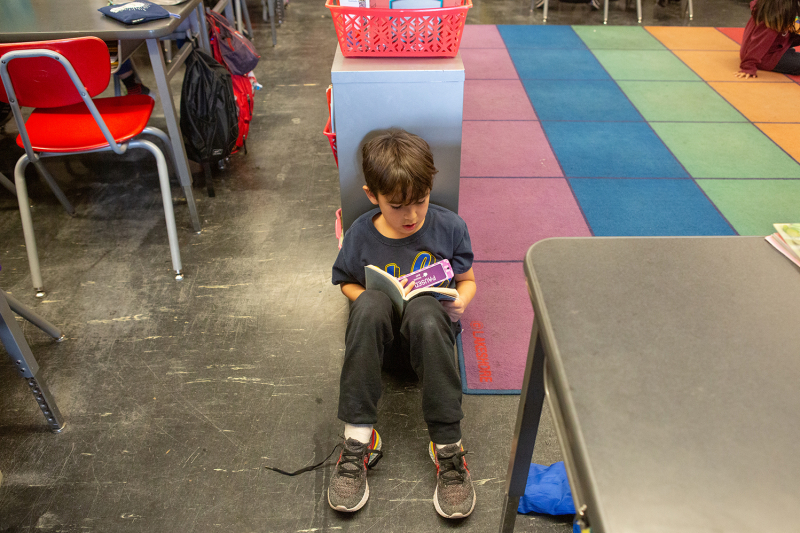

Researchers from the Walkout! Lab will survey incarcerated youth of color across the country about the identities they claim for themselves, including race, gender, sexuality and disability status. Next, the team will conduct in-depth, qualitative interviews with incarcerated students to get a clearer picture of their educational experience before and throughout their time in detention. In this phase, the researchers will use a method known as Education Journey Mapping to elicit the students’ trajectories.

“Journey mapping gives kids another modality to express themselves,” said Annamma. “Kids who’ve been in youth prisons may struggle with literacy, and they might have difficulty engaging with people, so we want to make sure they have a lot of ways to communicate with us.” The students can use timelines, physical maps, pictures or another method that helps them convey their trajectory from school to incarceration, and their hopes for their future.

“We’re trying to get at the hotspots that push them out of schools, and reflections about what prison education is like now,” said Annamma. “We have such large numbers of kids of color with disabilities getting routed into prisons. If we really want to make schools more equitable, we need to study the practices that push kids out and find different points we can shift.”

This research project aligns with another underway at the lab, part of a research-practice partnership between San Francisco Unified School District (SFUSD) and the GSE that began in 2009. In this study, Annamma and her team are investigating the overrepresentation of Black students at SFUSD in special education and suspensions, to help the district address the disproportionality. When the district approached her, Annamma took on the project with one condition: Rather than relying on existing data that focused on adults’ reflections, she would collect data from the students’ perspective.

“Kids, especially the ones who have been pushed to the margins, are in the best position to tell us what works and what doesn’t,” Annamma said. “In all of my work, I want their voices to be at the center.”

Faculty mentioned in this article: Subini Annamma