Innovation | K-12 | Teaching

Letting students fidget can boost creativity, Stanford-led research finds

For generations, teachers have urged restless students to sit still and stop squirming. New research suggests that those fidgeting children may not be distracted after all – and that they’re likely to be more creative than they would be otherwise.

A Stanford-led study of sixth and seventh graders finds that the vast majority of the students came up with more creative ideas when they were allowed to fidget at their desks than when they were instructed to sit still. What’s more, granting them permission to move freely in their seats did not diminish their ability to focus or remember information.

“If you look at a classroom of kids, there’s so much movement, and we have this assumption that if kids are moving around, they’re not paying attention,” said the paper’s lead author, Marily Oppezzo, PhD ’12, an instructor of medicine at the Stanford Prevention Research Center who earned a doctorate in educational psychology from Stanford Graduate School of Education (GSE). “This research suggests it can be beneficial in some ways for kids to do what their body needs.”

The paper, authored by a team that includes scholars from various disciplines across Stanford as well as industry technologists and a local educator, was published in the Journal of Educational Psychology on Nov. 17.

“It seems intuitive that people’s physical bodies would influence their thought processes,” said study co-author Dan Schwartz, dean of the GSE and faculty director of the Stanford Accelerator for Learning. “But it’s rare to demonstrate that, let alone in a way that has clear practical implications.”

Marily Oppezzo

Measuring the impact of natural movement

The new study, which involved two experiments with middle school students at a Bay Area private school, expands on research into the cognitive impact of unstructured movement.

Past research has primarily focused on adults, including a landmark 2014 study by Oppezzo and Schwartz, who found that creative thinking improved in college students and other adults who walked at a self-selected, natural pace.

Small studies involving K-12 students have explored the use of objects such as fidget spinners and stability balls, particularly for students with ADHD, but their findings on cognitive effects and academic performance have been mixed. The new study led by Oppezzo adds to researchers’ understanding by investigating the impact of dynamic seating on young learners’ creative thinking in particular.

In this study, researchers assessed sixth and seventh graders’ creativity under different sitting conditions by measuring “divergent thinking,” a process of generating many different ideas and solutions to a problem.

Researchers gave the students four minutes to generate as many alternate uses as possible for everyday objects, such as a brick or a tire. A response counted as “creative” if no other student in the study came up with it. The researchers also only considered responses that were a viable use of the object, and rejected vague ideas (like “play with it”).

To avoid any bias favoring more talkative students, the researchers measured creativity using a “novelty ratio” for each student: the number of novel ideas divided by the total number of ideas the student came up with.

“If a student had 10 ideas total while they were sitting still and two of them were novel, and then when they had the freedom to move, they had 20 ideas and four were novel – the measure would be the same, not an increase,” Oppezzo said. “We wanted to make sure [the measure] wasn’t about loquaciousness.”

For each of the two experiments, in addition to divergent thinking, the researchers measured a second cognitive process: The first test, with 32 sixth graders participating, included a memory task; the second, with 43 seventh graders, measured focused attention.

“We did that to eliminate any ‘halo effect’ explanations. If everything improves, you can’t say whether there’s a selective mechanism at work,” Oppezzo said. “We wanted to identify which particular tasks might benefit from the movement, and also test whether there could be a negative effect.”

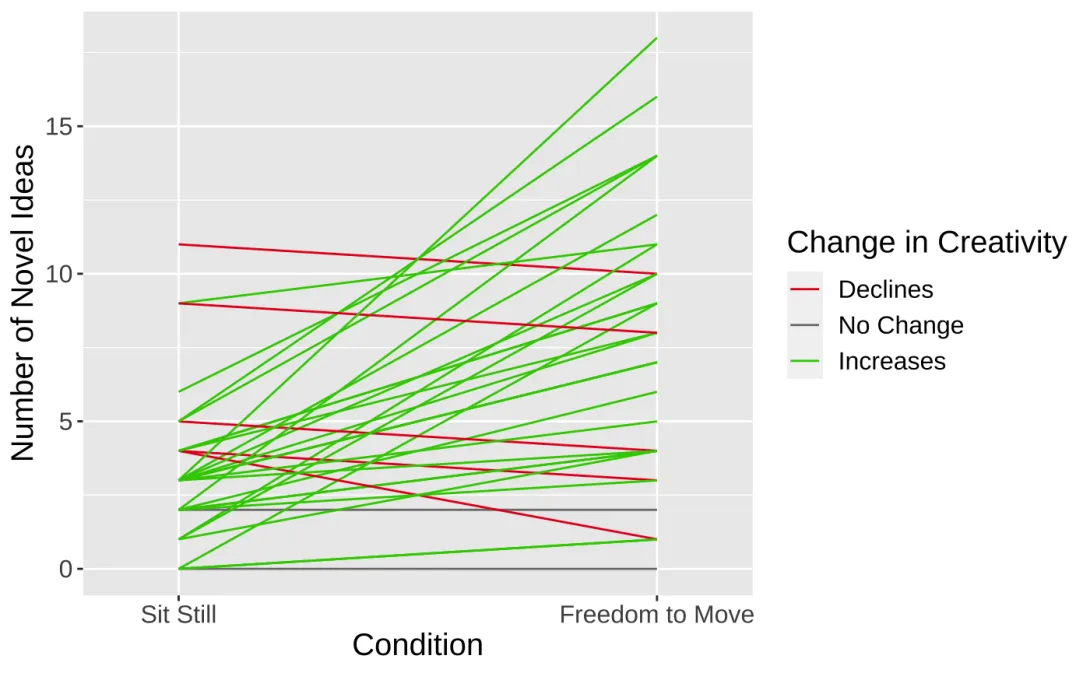

The vast majority of students in the study showed an increase in novel ideas (represented by the green lines), with only a handful of exceptions (in red).

Sitting still vs. freedom to move

In the first experiment, the researchers measured the sixth graders’ divergent thinking and memorization under two conditions: 1) seated in a regular classroom chair and directed to stay as still as possible, and 2) seated in a “wiggle stool” that allowed rocking and told they could move freely in whatever way felt natural.

The study design had each student participating in both conditions, with each student’s performance in one condition compared only against how they did in the other. The aim was to eliminate any individual differences, like mood or personality, that could affect the results.

For the memory task, the researchers used a test based on the “generation effect,” a phenomenon that predicts people are less likely to remember words they read than those they have to work to produce. The students were given word pairs, half of which required them to generate the second word by filling in blanks in the place of letters (for example, “fast: r-p-d” vs. “fast: rapid”). Students were then prompted to recall all of the words – those they read, and those they had to generate.

Generation consistently outperforms reading on memory in studies, so if the effect was not replicated evenly across the two sitting conditions, the researchers would conclude that the conditions were influencing students’ memory in different ways.

The researchers found that roughly 80% of the students were more creative when given the freedom to move, generating more novel ideas overall as well as a higher ratio of creative ideas per total ideas generated. The memory performance was unaffected across conditions.

But was it that the freedom to move helped creative thinking, or that the constraints of sitting still hurt it? To help answer that question, the researchers added a third condition to their second experiment: “sit as usual,” with a regular chair, which would limit the freedom to move without imposing a psychological restriction.

To evaluate focused attention for this experiment, students were asked to match numbers to letters according to a key they were given, and told to work as quickly as possible without making errors.

The findings of the second experiment replicated those of the first, with about 82% of students generating more novel ideas in the freedom to move condition compared with sitting still. Adding the “sit as usual” condition revealed a linear trend: Students in that scenario generated more novel ideas than they did sitting still but fewer than they did with freedom to move – leading the researchers to conclude that not only did the freedom to move benefit creative thinking, but also that suppressing movement potentially hampered the process.

The experiment also found no significant change in students’ focused attention from one condition to another.

Changing norms around classroom seating

Students wore accelerometers for tracking their activity levels during the study, and individual differences in the extent of movement did not correlate with creative output, the researchers found.

“Different kids had different levels of wiggling when they were allowed to do so. But the amount they wiggled did not predict creativity,” Oppezzo said. “If you allowed the kids to wiggle to their natural level, they had more creative ideas. The point is not to force everybody to fidget.”

The researchers did not collect information on the students such as test scores, racial and ethnic identity, ADHD diagnoses, or parental education or income. But the researchers said the consistency of effect across 80% or more of the students suggested it generalizes well across many individual differences.

Because students for this study were pulled out of class individually and tested in a separate room near the classroom, Oppezzo acknowledged that an important direction for future research would be to investigate the impact of a freedom-to-move approach at a classroom-wide level.

“How distracting is it for teachers to have students wiggling around in their seats?” she said. “Testing this in a full classroom setting could also show whether students are distracted by their neighbors moving around, since this study only showed that their own movement wasn’t affecting their attention.”

Still, Oppezzo hopes their findings will help to change perceptions and norms around classroom seating, as research into optimal learning environments evolves and school leaders explore new design possibilities.

“Modern classrooms, like offices, are changing. What should the classroom of the future look like?” she said. “I hope this research is a step toward opening people’s minds.”

In addition to Marily Oppezzo and Dan Schwartz, the study was co-authored by Rocky Aikens, a senior statistician at Mathematica who received her PhD in biomedical informatics at Stanford; Jessie B. Moore, a doctoral student at the UC Berkeley School of Public Health and former project manager at the Stanford School of Medicine; Joss Langford, chief technology officer and founder of the digital health company Activinsights; Michael Baocchi, an associate professor of epidemiology and population health at Stanford; James J. Gross, a professor of psychology at Stanford; and Ilsa Dohmen, chief academic officer at Hillbrook School in Los Gatos, Calif.