Intellectual disabilities and college: Envisioning bright futures

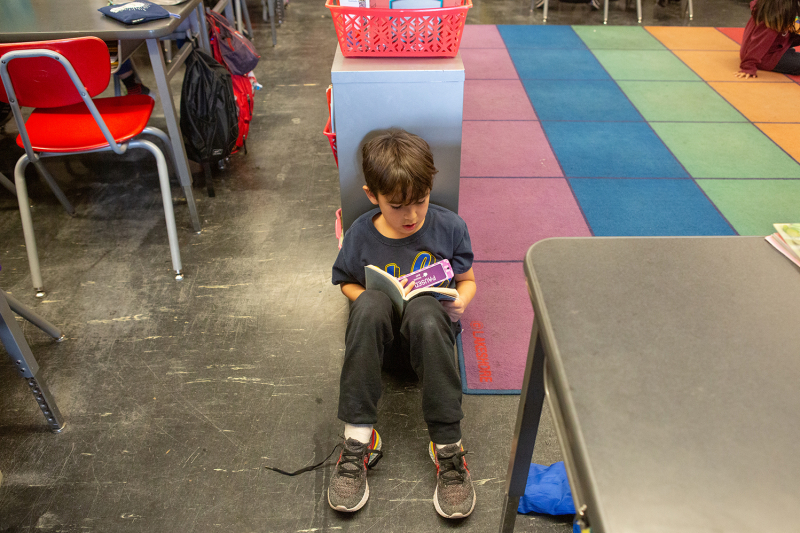

Believing that students and children with intellectual and developmental disabilities (IDD) can achieve their goals in academic and social settings is a major part of ensuring that they will, according to Stanford Professor Christopher J. Lemons.

“They really do have limitless potential,” he told School’s In co-hosts GSE Dean Dan Schwartz and GSE Senior Lecturer Denise Pope. “One of the phrases that we like to think about with this group is ‘presumed competence.’”

And that’s not just optimism. Lemons’ research includes an ongoing study with 3-, 4-, and 5-year-old children whose parents read to them to help increase their vocabulary. The study has shown that students with IDD can learn new things with appropriate support at home and in the classroom. Phonics has long been the most effective way to teach reading, but, for decades, children with IDD were instead taught to read by matching pictures to words. More recent studies, including by Lemons, have shown that phonics can work for children with IDD as well.

Teachers who see that children with IDD can grasp basic concepts are more likely to push them to advance. Conversely, when a child reaches kindergarten without basic literacy concepts, the teacher may opt to withhold reading instruction until the child is older.

“That’s the biggest mistake that educators can make with this population,” Lemons says. “You should not delay reading instruction just because they don’t appear to be ready . . . the earlier [they] get reading instruction . . . the better they do in terms of long-term success.”

Among other research projects, Lemons has piloted a post-secondary residential program for students with IDD on Stanford’s campus. With funding from the Department of Education, he plans to expand that to a four-year experience complete with specialized coursework designed to facilitate independent living, artificial intelligence experiences, digital literacy training, plus opportunities for the social activities life on a college campus entails. Crucially, the program will also include employment pathways.

“When we give these individuals tools, strategies, believe in them, help them belong,” Lemons said, ”they will blow us out of the water every single time.”

Chris Lemons (00:00):

When we give these individuals tools, strategies, believe in them, help them belong, they will blow us out of the water every single time.

Denise Pope (00:14):

Welcome to School's In, your go-to podcast for cutting-edge insights in learning. From early education to lifelong development, we dive into trends, innovations, and challenges facing learners of all ages. I'm Denise Pope, senior lecturer at Stanford's Graduate School of Education and co-founder of Challenge Success.

Dan Schwartz (00:37):

And I'm Dan Schwartz. I'm the Dean of the Graduate School of Education and the faculty director of the Stanford Accelerator for Learning.

Denise Pope (00:47):

Together, we bring you expert perspectives and conversations to help you stay curious, inspired, and informed. Hi, Dan.

Dan Schwartz (00:58):

Well, Dr. “Limitless Potential Pope,” It's good to see you.

Denise Pope (01:02):

I like that I have limitless potential.

Dan Schwartz (01:03):

I think so.

Denise Pope (01:04):

I know that we're talking about this today. You know, in education, you hear this a lot. You hear, "I want my kid to fulfill his or her potential," or, "Our mission is to have every kid at the school fulfill, you know, their potential." And I don't... How do you even measure someone's potential? What is that even about?

Dan Schwartz (01:25):

I don't know. There's a lot of standardized tests that think they're doing that. But, uh, I think the big fear is you underestimate people's potential.

Denise Pope (01:34):

Hmm.

Dan Schwartz (01:35):

Right? At, at the level of the individual, if you overestimate, they'll get new opportunity. If you underestimate, the door gets shut on them, because you say, "Well, they, they don't have the potential to succeed in this endeavor." And so, this has always been a concern in the area of disabilities, intellectual disabilities. We're fortunate today to have someone who's gonna help us think about fulfilling children's potential.

Denise Pope (01:59):

I love that. So our guest today is Chris Lemons. He is a professor of learning differences and special education at the Graduate School of Education, and he applies the science of learning to new techniques for teaching and supporting students with intellectual and developmental disabilities. And you might hear in this show, we might shorten that intellectual and developmental disabilities and say IDD, just to shorten it. And so, Chris, welcome. Welcome, welcome. We're thrilled to have you here.

Chris Lemons (02:28):

Thank you. Glad to be here.

Denise Pope (02:29):

And I think, like, a first obvious question is for people who really aren't familiar with maybe some of the characteristics of IDD. Could you just walk us through learners with IDD? Tell us what we might see.

Chris Lemons (02:41):

So you did point out, um, correctly that in special education, we love our alphabet soups.

Denise Pope (02:47):

(Laughs).

Chris Lemons (02:47):

We love, you know, to have abbreviations for everything. So when I most often talk about intellectual and developmental disabilities, IDD, I am referring to students in K to 12, where really in special education students can receive services under IDEA [Individuals with Disabilities Education Act] up to their 22nd birthday, but they are students who qualify as having an IQ that is two standard deviations below the mean. So that would typically be an IQ of 70 on a test that has a 100 mean, which is average, and that they have demonstrated some lack of adaptive behaviors like self-care, safety, things like that. So many individuals with Down Syndrome would qualify under that category. Some students with autism would qualify. When I was a teacher in the late '90s, um, the definition of autism was a little more restrictive than it is now, so those students would have been students with intellectual disability and autism.

(03:42):

Now that range is a lot broader, but basically these are students that just like y'all started the show, you know, they really do have limited, or limitless potential. And, um, one of the phrases that we like to think about with this group is presumed competence to really have educators, you know, presume that the student has the competence to do a variety of tasks. So that's kind of the population of, uh, learners that I'm talking about.

Dan Schwartz (04:06):

So a great example of this is your work on reading, where, if I have it correct, children with IDD can still learn to read?

Chris Lemons (04:14):

Absolutely.

Dan Schwartz (04:15):

This is, you know, I, it's kind of surprising until you think about it, that sort of intellectual functioning and the ability to recognize letters are quite different.

Chris Lemons (04:24):

Yes.

Denise Pope (04:24):

Oh, wait, I would not know that. I think they're totally related. So this is news to me and very exciting.

Chris Lemons (04:30):

So I think, you know, in the past, so let's say 20, 30 years ago, a lot of people would have thought people with intellectual disabilities cannot learn to read through the way that we teach most people to read, which is a phonics-based approach, understanding the sounds in our spoken language are broken into small pieces. We map those onto letters. It seems kind of cognitively complicated.

Denise Pope (04:51):

Yeah.

Chris Lemons (04:52):

Um, so in the past, um, students with intellectual disabilities were taught by a sight word approach. So just, here's a picture of a word, this is a picture of a dog, that word is dog, match. It's a very effective way to teach a small number of words. Actually, you can probably get, you know, up to 100 words that way, but you obviously can't learn to read every single word you've never been taught just by matching it to pictures. We know that a phonics-based approach is more efficient and effective for all learners. So a lot of my early research did focus on trying to understand, can we make phonics instruction more effective, specifically for children and adolescents with Down syndrome? And through that line of work, we demonstrated that phonics-based approaches are still the most effective for this population of learners and they can learn to read.

(05:37):

And I will say, I do not think I've ever run a single study where there weren't two or three kids that blew us out of the water and we had to scramble to create more advanced materials, because they learned faster (laughs) than we wanted. So, you know, kind of annoying when you're the researcher having to create new stuff, but, you know, fabulous that the kids are learning. And so, I will say, we do also know that a lot of our learners with intellectual disability do struggle with generalizing. They understand, they struggle applying comprehension strategies, and a lot of that is based on prior knowledge, background knowledge, and language skills. We have to kind of supplement the reading with those things as well, but the basics of how we teach reading are pretty much the same.

Dan Schwartz (06:16):

So is that a surprise to you, Denise?

Denise Pope (06:18):

I mean, it is a surprise. It's a really pleasant surprise. I mean, I, first of all, the phrase presumed competence might be my new favorite phrase in education, Chris. I love that. I feel like with every kid, we should presume competence. But particularly with the kids with IDD, I would assume it would be even harder because, like you said, they don't have a lot of background. I mean, let's just go to reading for a second. We're told to read to kids as parents, right? I'm assuming parents who have kids with, let's say, Down syndrome are reading to their kids. And I know that that has something to do with learning how to read, and maybe that's giving them some background information, but what you're doing is a little bit different. You're helping and providing some of that background information to augment, yes? Am I understanding that right?

Chris Lemons (07:06):

Correct. I mean, we have studies that span a variety of ages. We're currently running, uh, an intervention study for kids three, four, and five years old. It's a book reading intervention that their parents are delivering, and the primary focus is to increase the child's vocabulary. So an evidence-based practice that came out of the UK, and we're trying to replicate it here to see what aspects we might need to tweak. Specifically, there were several British words (laughs) that we needed to change.

Denise Pope (07:32):

(Laughs).

Chris Lemons (07:32):

But, you know, making sure that families understand, like, when reading books, it's not just about plowing through the book, but it's focusing on understanding language, understanding on the context, getting students or children's spoken language to go from, you know, one word phrases, to two, to putting things together. So when we can give families those strategies, those little guys and gals, whenever they transition into kindergarten, it's much more likely when they hit the kindergarten classroom, if they know how to read their name, they might know a letter or two or three, they do understand that print represents meaning and spoken language.

(08:11):

Those kids, teachers are more likely to say, "Ah, you're a potential reader. Let's get you into a reading group." Kids who come without that, some teachers say, "Oh, you know, little Dan here is not quite ready for reading. Let's try reading in third grade or fourth grade."

(08:25):

That's the biggest mistake that educators can make with this population. You should not delay reading instruction, just because they don't appear to be ready.

Denise Pope (08:33):

Mm.

Chris Lemons (08:34):

And we've seen through a lot of our studies that the earlier you get reading instruction into the, you know, program for these kiddos, the better they do in terms of long-term success of moving into education, post-secondary, being independent, employment and those things.

Dan Schwartz (08:48):

This does take us to the idea that children with IDD might experience college, and I know you've been working on that. So Chris is looking at their potential, now he's saying, "Do they have potential to benefit from, uh, a college experience?"

Denise Pope (09:03):

So are we talking about all kids with IDD, Chris? Help us understand this, because this, this is kind of a new concept.

Chris Lemons (09:10):

Yeah. Okay. So the idea here is that when we think of students with IDD, when they are in special education, in K to 12 education, the priority, or one of the priorities in IDEA, the Individuals with Disabilities Education Act, is to educate them alongside their peers who do not have disabilities, same age peers, as much as possible. We know that that is really great for them, it's really great for their peers. And so, whenever kids turn 19, most students exit high school and go to military, employment, some go to college. Students with ID often stay in high school until they turn 22. So you can imagine that probably doesn't sound terribly fun if all of your friends are leaving and you're stuck there. So we want additional pathways for these young adults to be able to stay with their peers and increase their education. And so, college pathway is one of those pathways.

(10:08):

Do I think every person with ID should go to college? Absolutely not. Do I think all humans should go to college? Absolutely not. But it should be a pathway for students who want it. And so, I think your question was kind of the, which kids are we talking about? So what we're hoping to design here is a four-year residential program that is, will focus a lot on unique specialized courses for the students that are focused on employment, independence, social living, but also they will take usually about one traditional course per quarter where we, we will give the faculty member and the students some support to make that a meaningful learning experience, but really the aim is to continue to enhance the learning that they had in K to 12, so that when they're done with our program, they're able to get a really meaningful, joyful job, that they have great social experiences, they're embedded in the community.

(10:58):

And "Think College" is a great resource for anyone who's wanting to learn more information. It's the National Coordinating Center for the TIPSIT grants, which are transition programs for students with intellectual disability through the Department of Ed, and we just received one of those grants to launch our program. And they have a lot of statistics on their website that are really powerful, that show the drastic increase in employment when young adults with ID go through these programs, the drastic increase in happiness and social connections and independent living. And so, I think these programs have incredible value, but not only for the students who are enrolled in them, but the peers and the faculty members who are also engaged with the program.

Dan Schwartz (11:38):

I've seen your crew in the summer out on the fields and the, you know, the athletes really like to work with, with the kids and everybody's having a very good time. You can see it.

Chris Lemons (11:49):

Yeah.

Dan Schwartz (11:49):

Yeah, it's really sweet.

Chris Lemons (11:51):

It is pretty sweet. So we've been doing the summer residential program three years now to get us ready for our program. And as you know, Dan, I lived in the dorm a couple of summers with that program, quite an eye-opening experience. But yeah, I think it's just amazing when we bring these young adults to campus and have them interact with traditional Stanford undergrads, and athletes are some of the best.

Denise Pope (12:12):

Well, and also you would think that a lot of these kids probably haven't lived by themselves before. I mean, and just even that alone, nevermind taking the classes, right? Just coming and living in a dorm environment has gotta be a huge learning experience for these kids. And you've found that they've been able to do that.

Chris Lemons (12:30):

Yeah. I mean, it's a learning experience for them. So I can think of one young man that w- came to our summer resident program this summer and at the beginning of day one, he pulled me aside and he said, "Chris, like, I don't think I can do this. I think you need to call my parents. I need to go home."

Denise Pope (12:43):

Aww.

Chris Lemons (12:43):

And I was like, "Come on, dude, you can do this."

(12:46):

And so, at the end of the week, he's like, "I can't believe I did it. Like, I can do this. I can live on my own. You know-"

Denise Pope (12:50):

Aww.

Chris Lemons (12:50):

"... I was able to take care of my needs."

(12:52):

And then, it's also eye-opening for the parents. We have an example of a young woman that she's just amazing and she loved the program and just took off, but her dad was really worried about her and a few days in called and said, you know, "Can I drop by and check on her, because she's not responding to text or anything?" And I was like-

Denise Pope (13:08):

Typical college student, by the way. (laughs).

Chris Lemons (13:10):

Right, which is what we want. We want them to act exactly like tr- you know, typical college students. And so, dad comes during our little, you know, 30 minute visitation period before dinner and the daughter is like, "Dad, what are you doing here? I'm at college. Like, go home."

(13:24):

And so, he's like, "You're not responding to text or calls."

(13:27):

And he's like, "I don't have time. I have homework. I'm working with my friends."

(13:30):

And it's that, actually, I think that's one of my favorite stories, because it shows how young adults with ID, they act just like traditional college students, you know, when we give them the opportunity to do so. And I think it helps them see their own potential, but also very importantly to show the families that they don't need to wrap this immense protective bubble around them at all times, that we can give them some freedom to experience the real world, which is gonna include some bumps and failures along the way, but that's what we all experience and that's what they also need to experience.

Denise Pope (14:03):

I love that so, so much.

Dan Schwartz (14:05):

So I, I still think this will be inconceivable to people.

Denise Pope (14:15):

What, what parts?

Dan Schwartz (14:16):

Uh, here you have s- ... Well, you have Stanford and, you know, one response is, "Sorry, I really care about these kids, but I want my kid to get admitted. And you're using up spaces for those kids who didn't take every AP course in existence."

(14:33):

So that, that's one, and I think that's probably a misconception. Another one is, "I'm listening to this. I have no idea what they're doing during the day."

Chris Lemons (14:42):

Okay. So the idea here is, so one, it's not a zero-sum game. It's not like these students are taking away a slot in the freshman class for traditional students. The students that we're going to enroll will be enrolled in our program, which is gonna be called the Stanford Cardinal Academy or SCA. They are not earning a Stanford Bachelor's degree, so they're not in competition with the traditional undergrad. But in terms of what they're doing, they will have a specialized sequence of courses. So those courses, again, will just be for the cohort of the SCA scholars, so our students, that will continue working on basic skills like reading, writing, and math. We will work on employment skills. They'll have internships on campus first two years, off campus last two years. They will have courses on health, wellness, sexuality will be in there, and independent living, dorm living.

(15:34):

So they'll have a lot of coursework there. Again, they'll take about one traditional college course per quarter. A good example of this, um, UC Davis is, often we consider them our sister program. Currently, they're the only four-year residential program in the state, and we've leaned a lot on them for our development. So there was one student there who was African American, really wanted to know about Black history, and they have a minor there, and so he actually completed all of those courses, and that was something he was interested in, he wanted to learn in. In the course, our staff will work with the faculty member to say, "Okay, this is your syllabus. Now let's think what are the unique or specific learning objectives for this scholar?"

(16:18):

And then our staff will help that faculty member with any adaptations that need to be made, and our scholar will have what we're calling a Stanford Cardinal Academy navigator, who's an undergrad mentor that will help with tutoring and homework and things like that. So they will have specialized coursework that helps them meet their unique needs, so they'll be successful whenever they graduate. But the importance of being on the college campus is that they have all of the other experiences that you get at college. And so, that is not just coursework, it's social interactions, making friends, clubs, you know, athletics. There are all kinds of things you learn at college and getting to know people who have a different lived experience than you. And so, we want to offer them all of the benefits that kids get out of college, in addition to their degree.

(17:07):

But also very importantly, you know, I personally, and I think y'all do too, value the idea of creating a more inclusive world, you know, for people with intellectual disability that they are included in society. And I truly think if we at Stanford think we prepare the best and brightest lawyers, doctors, teachers, artists, if they have the experience of making a friend and getting to know a student with ID during their college years, they are much more likely when they graduate and go into the workforce to say, "Hey, I'm a doctor in this office. Why do we not have any staff with ID?"

Denise Pope (17:40):

Mm.

Chris Lemons (17:41):

"I'm, you know, gonna go into advertising. Why don't we have any interns that have ID at our place?"

(17:45):

And I think it's a great potential to, you know, have a good impact on changing the world, because I think many of us, the college years are some of our most formative years of who we become as an adult. And so, injecting that experience I think will just make the world a better place.

Denise Pope (18:01):

Love it.

Dan Schwartz (18:01):

You brought up employment. So, uh, something you can do if they're with you on the college campuses, you can sort of prepare them for specific settings that they would move into, right? So you probably could do some specialized instruction that prepares them to take a job. Am I right? Like, are you working with employers to figure out how to set a pathway for them once college ends?

Chris Lemons (18:24):

So one of the things we know about people with IDD is they do struggle often with generalization. So it's the idea if I learn how to do a task in one way in one room with one adult helping me, and then I try to do it in a different room with different materials with a different person, sometimes that's hard. So one of the challenges with many of these programs that currently exist is that if we train you how to do a set of skills and then don't really make a strong connection with the employer, it's really hard for that student to be successful. So one of the things we're doing, we're conducting a parallel series of studies and a line of research on the side of this program to really go to places. There are several, you know, Silicon Valley companies that are really excited about increasing the number of people with IDD they employ, and those companies are very eager to understand, one, how they can craft more meaningful, joyful jobs.

(19:18):

Unfortunately, many of our young adults, you know, it's like, great, your job is to sit in the copy room and put paper in it whenever it's out.

Denise Pope (19:25):

Mm.

Chris Lemons (19:25):

I don't think any of us would want to be doing that job for many hours a week. And so, one of my colleagues often says our graduates often get the three Fs, which is filth, food, and flowers. Those are the kind of jobs (laughs) that we get.

Denise Pope (19:38):

Aww.

Chris Lemons (19:38):

Those aren't great jobs. And so, we're working with some of our industry partners to say, okay, you have this team of eight people, let's think of all the tasks those eight people do. What are that tasks we can pull off and bundle into a job that someone would actually be really excited to go to work to do? And we know, again, going back to this presumed competence and limitless potential, our students can do a ton of jobs if we give them the training and support. And so, we're really working better to partner with industry so we're having our training actually represents what they're doing. I would really love to be able to add two years after graduation, where we do some induction support on job support coaching.

(20:20):

And then it's also very important, I think, that it's important to also offer some training for the other employees in the office. You know, how do you interact with the young man with Down syndrome? When he's coming into the job environment, how do you give them feedback? Many of our young adults with ID, when they get a job, they don't get fired, because they can't do the job. They get fired, because they're being somewhat socially inappropriate. They're having a crush on, you know, Denise, she's really cute, I'm gonna go flirt with Denise on every break I get. And then Denise is like, "Can you get this kid to leave me alone?"

Denise Pope (20:53):

Mm.

Chris Lemons (20:53):

And so, being able to give Denise some tools to communicate with the employee with ideas also very helpful. And so, we're working with the industry partners now to do both of those things. And I think that will make our program much more effective.

Denise Pope (21:07):

So I have a niece who does a job like this in Massachusetts. She works at a school for kids with IDD and when they graduate, they take an extra year and my niece is the person who goes with them to their job, you know, gives them j- job training for what their job is gonna be, but then actually goes with them to their job, does a little bit of that like transition time with the company, with the kid, often is the driver ,because a lot of these kids don't drive, uh, works out, you know, this is how you're gonna get there on the bus. Like every, from soup to nuts, basically, to get them to be feeling really, really successful in their jobs. And it's just all of us need that little extra transition time, right? And someone's figured out, "Oh, this is how we do it right, before we just send people out into the world. Let's give them a little bit of scaffolding. Let's help that." So it's pretty exciting.

Dan Schwartz (21:59):

So I, I, I can't resist switching just for a second, Chris. It's all AI all the time here at Stanford. And, uh, I'm fairly convinced that one of the important things AI will do is to help kids who have special needs of various types. And so, I was wondering, do you share that belief or have you seen examples? Like, am I just dreaming?

Chris Lemons (22:22):

I absolutely share your belief. I think that, um, so in our proposal to the Department of Education that was funded, we've proposed developing an AI and digital literacy credential for our graduates. So they will have the option to go through that pathway. I think AI really has an incredible potential to level the playing field in many ways for the jobs that young adults with ID can do. So if we could train them how to use AI to make their emails more professional, to summarize some documents. You know, there are many basic office tasks that if you know how to use AI to do it, you can actually be more successful and more efficient.

(23:00):

So we're currently building that program and also working with some AI folks to really better understand how to do it in a more meaningful way. So I think we have some work to do in the AI land to make sure that we're, you know, being ethical with it, that we're using evidence-based strategies integrated into AI, just not shiny bells and whistles, but I think there's a lot of potential that we can really use that tool to even further enhance the jobs that these young adults can do.

Denise Pope (23:26):

Amazing, right? And I mean, I can see it help summarize. You can ask a question. You can say, "I'm not sure what this means," and then it will tell you. It's, and as it gets better, it will be more and more efficient. So you have to train your kids how to use it, but you see it as a real level changing mechanism.

Chris Lemons (23:45):

Definitely.

Denise Pope (23:46):

Yeah.

Chris Lemons (23:46):

Definitely.

Dan Schwartz (23:47):

So as we wind down, I think I wanna change our usual model. Chris has been so phenomenally clear, I don't feel the need to give takeaways. What I want is I want Chris to tell the most inspirational story that he can think of, of sort of the limitless potential.

Chris Lemons (24:06):

I think a good inspiration for me is a young man named Dash or Dashiell Meyer, and he has been engaged with us through the Stanford Down Syndrome Center and some other things. So he's a young man. He's probably, he actually just turned 21, I think earlier this year. He has a young man with Down syndrome, and he's a good example of a kiddo that, one, he's a wrecking ball. He's a force (laughs).

Denise Pope (24:28):

(Laughs).

Chris Lemons (24:29):

He, he's just a little fireball, so no one's gonna slow this kid down. But he's a great example that when your parents believe in you and don't put a wall in front of you, when your educators believe in you and don't put a wall in front of you, can do amazing things. So he has served as a mentor for us where he comes in and, you know, talks to our young adults in the residential program, but he has spoken in front of the UN.

Denise Pope (24:51):

Mm.

Chris Lemons (24:51):

He currently makes movies. He does a lot of these really awesome little s- um, stop still movies, you know, where you, like, have little Legos and you move them, and then take a picture and move them, and take... He has this one awesome one on Star Wars. I'm sure if you Google him, you can find them.

Denise Pope (25:04):

(Laughs)

Chris Lemons (25:05):

He's in the Special Olympics ad campaign. So in San Francisco, I often see his face on the bus whenever I get on the bus.

Denise Pope (25:11):

(Laughs)

Chris Lemons (25:12):

And then, he's just this dynamic speaker that he goes around and does lectures about how, you know, the future is bright. And, you know, if you don't limit people, they can do amazing things. And he is one of many, many young people with intellectual disability that show this. But I think it's just this idea that when we give these individuals tools, strategies, believe in them, help them belong, that they will blow us out of the water every single time.

(25:40):

And I think that's actually the most exciting thing when I work with them is, like, even in the summer residential program over such a short period of time, the change you see is dramatic and exciting. And I think, you know, we'll just keep building that. And I... It's my favorite part of my job.

Denise Pope (25:56):

Aww. This show made me happy.

Chris Lemons (26:00):

(Laughs).

Denise Pope (26:00):

Thank you, Chris.

Dan Schwartz (26:00):

(Laughs).

Denise Pope (26:00):

Thank you so much for being here.

Chris Lemons (26:02):

You're welcome.

Denise Pope (26:03):

And thank all of you for joining this episode of School's In. Be sure to subscribe to the show on Spotify, Apple Podcasts, or wherever you tune in. I'm Denise Pope.

Dan Schwartz (26:12):

And I am Dan Schwartz.

Denise Pope (26:14):

Yay.

Faculty mentioned in this article: Christopher J. Lemons