“Just telling children to take a deep breath may not be enough – children need scaffolding. So we’re excited that we can also offer an easy-to-use tool to help kids learn this technique.”

How to calm a stressed kid? A one-minute video can help, according to Stanford researchers

It’s one of the first things parents and teachers tell a child who gets upset: “Take a deep breath.” But research into the effect of deep breathing on the body’s stress response has overwhelmingly ignored young children – and studies done with adults typically take place in a university lab, making them even less applicable to children’s actual lives.

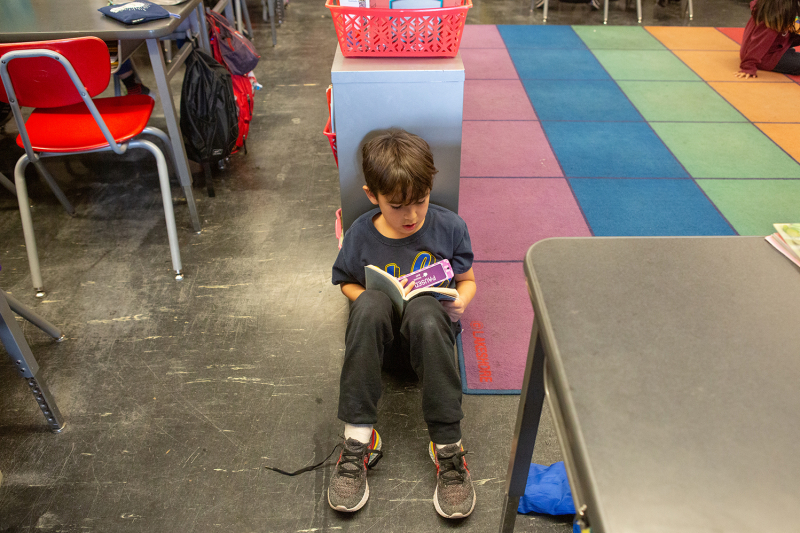

A new study by Stanford researchers is the first to show that taking just a few slow, deep breaths significantly reduces young children’s physiological arousal. By measuring the effects in naturalistic settings such as day camps and playgrounds, the study is also groundbreaking for its design, which more closely reflects a child’s experience than a study in a lab would.

What’s more, the short, animated video developed for the study is now freely available online, providing a proven tool that can be used in the classroom to introduce children to deep breathing as a way to self-regulate. It can also help parents prepare kids for a potentially stressful situation – a vaccine appointment, say, or a holiday gathering.

“This study is the first to show that taking a few slow, deep breaths in an everyday setting can have a significant effect on a child’s stress physiology,” said the study's lead author, Jelena Obradović, an associate professor at Stanford Graduate School of Education (GSE) and director of the Stanford Project on Adaptation and Resilience in Kids (SPARK Lab). “But just telling children to take a deep breath may not be enough – children need scaffolding. So we’re excited that we can also offer an easy-to-use tool to help kids learn this technique.”

The study, which was coauthored by GSE research associate Michael J. Sulik and doctoral student Emma Armstrong-Carter, was published on Nov. 16 in the journal Developmental Psychobiology.

Designing a realistic field experiment

Mindfulness practices that incorporate deep breathing, such as yoga and meditation, have found their way into the classroom at many schools. But prior to this study, research had not clearly shown whether slow-paced breathing itself could significantly alter a young child’s physiological stress response, the researchers said.

They set out to isolate the activity of breathing and investigate its impact – taking practical considerations into account, including the likelihood that young children might not have the capacity for even a couple of minutes of deep breathing, and that they would need help learning how to do it.

“When you ask young children to take a deep breath, many don’t really know how to slowly pace their inhale and exhale, if they haven’t had any training,” Obradović said. “It’s not intuitive for young kids. They are more successful in taking several deep breaths if they have a visual guide.”

To help elementary schoolers learn the technique, the researchers worked with a team of artists at RogueMark Studios, based in Berkeley, Calif., to produce a one-minute video. The animated video shows young children how to slowly inhale by pretending to smell a flower and to exhale by pretending to blow out a candle.

“From a pragmatic point of view,” Obradović said, “we thought a very short sequence, four breaths, seemed doable for this age group.”

For their randomized field experiment, the Stanford researchers recruited 342 young children – 7 years old, on average – with their parents’ permission, at a children’s museum, a public playground and three full-day summer camps in the San Francisco Bay Area.

Roughly half of the children were assigned to a group to watch the animated video with the deep breathing guidance. The rest watched an informational video that featured similar animated images but did not involve the breathing exercise.

All of the children were shown their assigned video in small groups, at tables set up adjacent to the site from where they were recruited, to maintain a natural setting for the study. Also in keeping with the real-life approach to the study design, the researchers did not monitor children or provide extra encouragement to implement the deep breathing instruction.

This “intention-to-treat” approach – analyzing all subjects, whether or not they engaged with the intervention – is widely considered to provide more insight into the potential effectiveness of the intervention once it is applied in everyday group settings, like classrooms, where not everyone is likely to take part, Obradović said.

Measuring the body’s response to everyday challenges

Researchers measured two biomarkers in all of their recruits: heart rate and respiratory sinus arrhythmia (RSA), which refers to the changing pace of the heartbeat when a person inhales and exhales.

RSA plays an important role in influencing heart rate, Obradović said, and it has been linked to children’s ability to regulate their emotions, focus their attention and engage in tasks.

“When it comes to measuring the effects of deep breathing on stress physiology, RSA seems to be the most appropriate biomarker,” said Obradović. “RSA is the only pure measure of the activity of the parasympathetic nervous system, the system we’ve evolved to help us deal with everyday challenges – the kinds of challenges that don’t require a flight-or-flight response.”

The change in the measures was profound: RSA increased and heart rate decreased only in response to the deep-breathing video, and the effects were greater during the second half of the video, which included most of the deep breathing practice. The children in the control group showed no change in either measure.

“Our findings showed that guiding a group of children through one minute of a slow-paced breathing exercise in an everyday setting can, in the moment, significantly lower the average level of physiological arousal,” Obradović said.

Further research should examine the effect of deep breathing in this age group after a stressful or challenging experience, she said. “But the fact that children of this age can downregulate their stress physiology even when they’re relatively calm offers promise that the technique will be even more effective when they’re frustrated or upset.”

Access the full version of the video, with an introduction to deep breathing, or a shorter video with the deep breathing practice only.

Faculty mentioned in this article: Jelena Obradović