Getting a head start

Jackson Rose was in seventh grade when he took a class at school that sounded interesting, an elective exploring the science of sleep and its impact on the brain. Two years later, he and a classmate, Caroline Walker, were invited to an international neuroscience conference to share the findings from a research project they helped develop, presenting their work alongside leading scholars and scientists in the field.

How did two teenagers end up exhibiting cutting-edge research at a major scientific conference?

Rose and Walker were students at Synapse School, an independent school in Menlo Park, Calif., that’s also home to the Brainwave Learning Center, a research-practice partnership in collaboration with Stanford Graduate School of Education (GSE). The on-site lab engages students with neuroscience in the classroom while advancing research in the field, bringing researchers, teachers, and students together to study how young learners’ brains respond to different learning experiences.

The center – which launched in 2019 as part of the Educational Neuroscience Initiative, led by GSE Professor Bruce McCandliss – is a fully integrated part of life at Synapse. Stanford neuroscientists collaborate with teachers to develop and conduct studies on cognitive development, including math and reading. Students learn about and watch their own brain activity, in real time, during research sessions. Researchers teach a unit on neurobiology for upper-level science classes, and host roundtable discussions for teachers on mind, brain, and education work.

The center also runs an immersive Middle School Research Assistant Program, where seventh- and eighth-grade students learn about research methods, receive training on how to use neuroscience equipment such as electroencephalography (EEG) to observe electrical brain activity, explore their own scientific interests, interact with scientists on a daily basis, and drive independent research projects.

From left: Radhika Gosavi, associate director of the Brainwave Learning Center; former Synapse students Jackson Rose, Arav Ramchandran, Anya Jain, Simran Thakur, Caroline Walker, and Alexandra Lu; and Elizabeth Toomarian, director of the Brainwave Learning Center. (Photo: Peter DaSilva)

Through the program, about 20 Synapse students have been supported in developing research projects over the past two years – which is how Rose and Walker’s work ended up at the 2023 conference of the Flux Society for Developmental Cognitive Neuroscience, an influential forum for professional scientists, graduate and postdoctoral students, physicians, and educators.

“Initially, we just thought it might be interesting for the middle school students to get an idea of the scientific method, the type of science we do, and what the field is all about,” said Radhika Gosavi, a trained scientist and associate director of the Brainwave Learning Center, who leads the research assistant program. “But it’s grown into so much more.”

Rose, for one, who has dyslexia, was curious about how a dyslexic brain might interpret information differently from a neurotypical one. As a seventh grader he started exploring studies on audiovisual integration – how the brain combines sounds and images, which early research suggests may differ between dyslexic and neurotypical thinkers. He worked closely with Gosavi to understand the scientific literature, shape research questions, and design an EEG study.

Then Rose and Walker, who joined the program the following year, were introduced to Lindsey Hasak, a GSE doctoral candidate whose research focuses on audiovisual integration in the process of reading. “I’d worked on the proof of concept for a few years of my PhD with neurotypical adults, and because of the students’ interest, we were able to expand the scope of the study,” Hasak said.

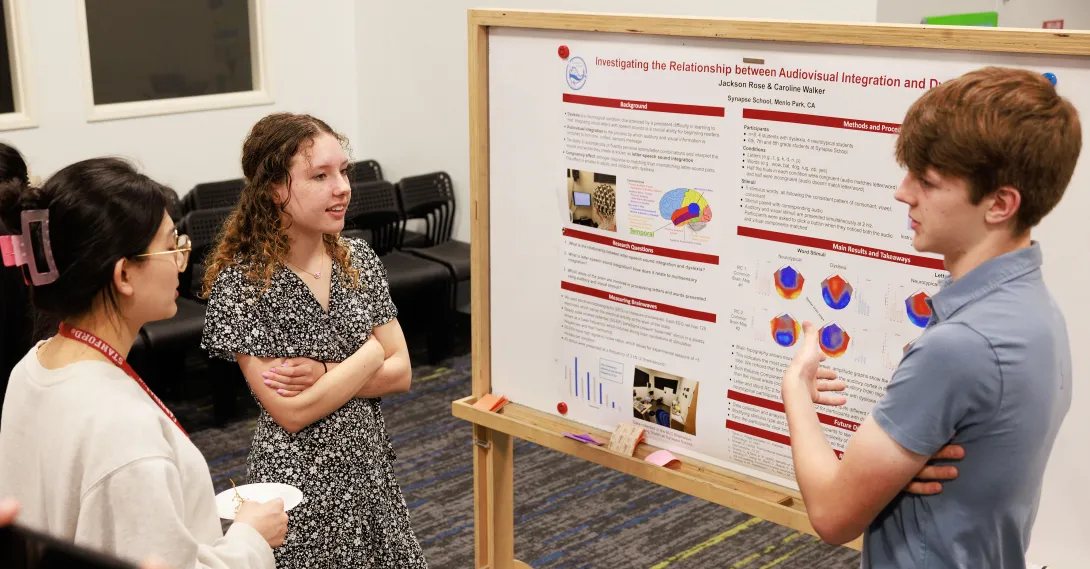

Rose and Walker recruited a study sample of fellow students with and without dyslexia, learned all the steps involved in an EEG experiment, and carried out the research using ethical protocols. The Brainwave Learning Center team worked with them to analyze the data, which shows differences in brain activity between those with and without dyslexia.

Caroline Walker (left) and Jackson Rose (right) discuss their research with Priscilla Zhao during a research showcase at Synapse School in 2023.

To give students the experience of presenting their work to an audience, the Brainwave Learning Center hosts a showcase at the end of each school year, drawing members of the school community, Stanford researchers, and others interested in educational neuroscience, including philanthropic organizations.

Students also submit their projects to local science fairs, and in 2023, three teams from the Middle School Research Assistant Program placed first or second in their category at the San Mateo County STEM Fair. One team went on to win first place in the cognitive science category at the California Science and Engineering Fair and qualified to submit their project to the Scientific Juniors Innovators Challenge, a national competition for middle school students.

The center also submitted the project Rose and Walker worked on to the Flux Society’s 2023 conference. Their submission was accepted – an accomplishment itself for any scientist – and Rose went to the event to present it at the poster session (Walker was unable to attend).

Their poster, one of more than 130 at the conference, won the society’s annual member’s choice award.

The research assistant program may introduce middle school students to the scientific method, Gosavi said, but its lessons aren’t only for aspiring scientists.

“Yes, the kids are learning science and scientific methodology. They’re coming up with creative ideas for research projects, and they’re winning science fairs and presenting at conferences,” she said. “But there’s also so much value added to their journey as a learner. When kids understand more about how their brain learns, it gives them a different perspective on the learning process, and a sense of ownership over that process.”

Rose has no idea whether he’ll pursue a career in science, but he agreed that the program had an impact well beyond the technical skills he developed. “Knowing how the brain works has absolutely changed the way I think about learning,” he said. “I could see myself as a learner in a way that I never saw before.”