Applying science to the question of how best to support working adults without college degrees

Flora, a 32-year-old single mother, faces a dilemma shared by many of the millions of American adults without a college degree.

She’s an excellent, highly motivated Tier 1 patient care representative at a health insurance firm. Now, her company is automating the work she does, and all of the Tier 1 positions will be eliminated. Her company will be promoting workers to Tier 2 patient care representative positions, something Flora has long desired. Unfortunately, she doesn’t have the degree the job requires. Flora earned a certificate in customer service at work and has six credits at a community college, but she can’t afford to go back to school.

The case study of Flora, who is a composite of research interviews and analyses of demographic data, helped guide a year-long effort by leading educators, convened by Stanford Graduate School of Education (GSE) and Stanford’s Transforming Learning Accelerator, to build an applied science to study the needs of “working learners,” a term that refers to adults pursuing paid employment and learning opportunities at the same time. The project culminated in nine recommendations, released Jan. 19, as part of a concise report to the National Science Foundation, which funded the endeavor.

“In a nutshell, we’re calling on government to play a leadership role in investing in an applied science of adult and lifelong learning, with a particular emphasis on understanding the educational needs of working adults who do not have four-year college degrees,” said Mitchell Stevens, a sociologist and professor at the GSE who is a leader of the project. “Most education research looks solely at the first quarter of life. The relationships between school, work and biography across the lifespan are a black box.”

In recent years, growing numbers of government agencies, nonprofits, for-profit companies, philanthropies and education institutions have developed programs to support working learners, spurred by the recognition that many adults without college degrees struggle with the impact of new technologies on work and the accompanying shifts in employment qualifications. But there is not yet a reliable way to evaluate the effectiveness of such programs, or even of determining whether they address the most critical challenges working learners face. The new report suggests that a major research initiative can determine how best to build an education system for working learners and how to invest public and private resources most effectively.

The recommendations include identifying new educational opportunities that may benefit workers throughout their working lives, promoting collaboration between researchers and businesses to better understand how new credentials are affecting hiring decisions; and developing data collection systems that will enable researchers to track transitions between learning and employment experiences as people progress from young adulthood to retirement. The report also recommends that such research be conducted by bringing together different stakeholders regionally.

Universities have a particular role to play as conveners, as employers and as educators and researchers, said Stanford University President Marc Tessier Lavigne when he spoke at the last of four discussion sessions in July that laid the basis for the new report. More than 180 education leaders from different sectors – government, private and nonprofit organizations, philanthropies and higher education – joined the online gatherings, which were convened with NSF funding by Stevens and the Transforming Learning Accelerator (TLA), a university-wide initiative to develop more equitable and scalable learning solutions. More than 35 Stanford faculty, staff members and students contributed to the project.

“To be effective, this must be a true cross-sector discussion because any science we develop requires the contributions of all of these stakeholders,” Tessier-Lavigne said at the July 28 meeting. “This is the beginning of a conversation that has the potential to make a difference for working learners for the long term.”

Daniel Schwartz, the I. James Quillen Dean of the Graduate School of Education who leads TLA, added in a recent interview that the report underscores the importance of work underway at Stanford. “We are creating new scholarship and learning solutions that bridge discoveries in education, neuroscience, humanities, data science, psychology, law and other fields to serve the needs of working learners,” he said. “We need to foster a future where all learners thrive – no matter their cultural backgrounds, zip code or age.”

The summer meetings led Stanford’s Office of Community Engagement to convene a campus conversation to explore how the university could deepen collaboration to support working learners. Megan Swezey Fogarty, Stanford’s associate vice president of community engagement and a participant in the July gatherings, explained, “We need to learn from leaders across campus, local community colleges, workforce development agencies and others how we can contribute to improve knowledge and skills not only for our own employees but for others in our region as well.”

Stanford Digital Education, a unit in the provost’s office, plans to help implement the recommendations of the report by piloting new programs, jointly developed with partners, for working adults. These programs could, in turn, yield new research opportunities in the emerging science of lifelong learning. Stanford Digital Education was launched last year to advance educational innovations for social impact and strengthen Stanford’s digital learning infrastructure.

Attention to working learners has grown in recent years as part of a sea change in thinking about national education policy. Since the Higher Education Act of 1965 expanded the GI Bill’s subsidy of college access for WWII veterans to include all citizens, the nation has sought to provide economic mobility by promoting college for all. However well-intended, that policy prescription has come to create its own problems. Key among them is that possession of a college credential has become a fateful divide in American life.

“On one side lie reasonably well-compensated jobs, better health, more stable families and more informed civic participation,” Stevens said. “On the other lie precarious, marginal employment, dangerous debt levels, strained relationships, depression and anger.”

In the hypothetical case study, Flora, the insurance employee whose job is being eliminated, finds herself stuck on the wrong side of that divide. To move ahead, she must consider a dizzying plethora of new educational services from big tech companies and smaller recently established edtech ventures, without data to help her choose a path that would improve her prospects.

“That’s a new frontier for the science of working learners,” said Stevens, noting that researchers will need data if they are to find answers. More and more of that data are proprietary and in the hands of private parties. The new report calls for researchers, government and other stakeholders to create new data infrastructures that can match the systems in place to evaluate K12 and higher education programs.

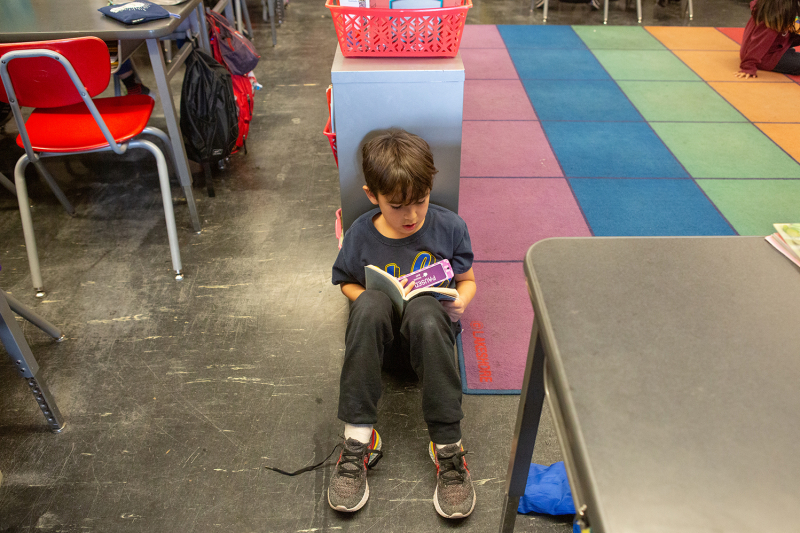

Like many working learners, Flora may decide to take advantage of online courses. Such offerings are convenient but may not necessarily be suited for the learning needs of older people. The use of digital education to serve working learners is still in relative infancy, and the report calls for identifying which approaches work best for which groups.

“To serve working learners effectively we have to marry their educational needs with our technological and human capacities,” said Matthew Rascoff, Stanford’s vice provost for digital education, who participated in the NSF-funded project and is one of the leaders in the Stanford Community of Practice on Working Learners. “Working learners need the scheduling flexibility of asynchronous online learning – but also need to connect with a supportive learning community that encourages growth. Our design challenge is to balance those needs in models that scale.”

“We’re still very much in the discovery phase,” Rascoff said.

Jonathan Rabinovitz is Stanford Digital Education’s communications director.

Faculty mentioned in this article: Mitchell L. Stevens