Helen Kim, ’92, MA ’93

Helen Kim oversees daily miracles at Eastside College Preparatory School where students defy the odds and go on to college.

It takes a village — and a school: Alumna’s education start-up offers new opportunity to East Palo Alto teens

Helen Kim oversees daily miracles at Eastside College Preparatory School where students defy the odds and go on to college

By Joyce Gemperlein

A picnic table in Palo Alto’s Mitchell Park is to Helen Kim ’92 MA ’93 what the garage is to the Silicon Valley entrepreneur: A symbol of starting simply but aiming high, entrepreneurial spirit, hard work and chasing a dream.

Twenty years ago Eastside College Preparatory School began with eight students and three teachers, including Kim, at that shady spot.

“I was 26 and knew very little about what I was doing,” Kim recalled. “Starting a school now seems more preposterous than it did at the time!”

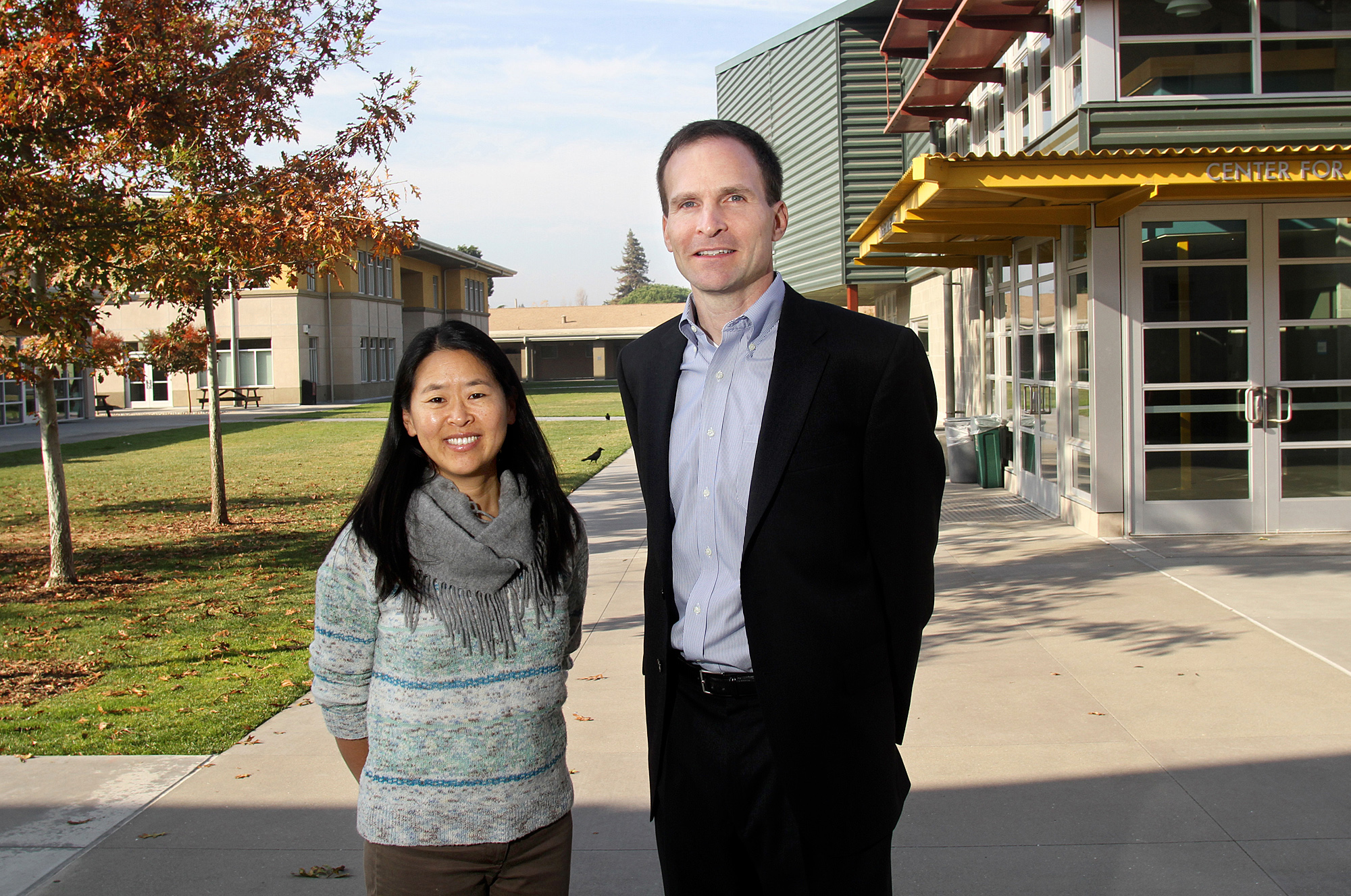

Still, spurred by what might be called youthful and blind optimism, Kim and Chris Bischof ’92 MA ’93 vowed to try to narrow the gap in educational opportunity faced by East Palo Alto students with low family incomes and even lower expectations for success as compared with their peers in neighboring communities.

Now, many milestones later, Eastside has its own campus, a dorm and 340 students in grades 6 through 12. Every graduate since 1996 has moved on to college; 99 percent of those are the first generation in their families to do so.

Kim, Eastside’s co-founder and assistant principal, will be honored for her key role in the school’s evolution with the inaugural Stanford Graduate School of Education Alumni Excellence in Education Award. The award recognizes transformational work in education and will be given to Kim, Jonathan Jansen PhD ’91 and Carla Pugh MD, PhD ’01 at an Oct. 23 reception during Reunion Homecoming week.

Friends immediately thought of Kim upon reading the announcement seeking nominations for the award, and Amy Reilly ’96 ‘MA 01 took the lead in submitting the nomination.

Reilly, who teaches English at Eastside, said that the concept of beginning and ending a workday and having a defined “job” does not apply to Kim.

“Eastside is Helen’s joy. It is not a job to her; it is her state of being,” said Reilly, who describes her as “the necessary glue that binds our school community in the tumultuous journey toward social change. She is a steady and firm partner for students, families and teachers, shining a light to guide everyone on a common mission of academic success.”

Kim's philosophies embody the culture of Eastside.

She said: “Our bread and butter is being an organic team effort in which students buy in and work hard to realize that they have a role in the trajectory of their lives. So much of our conversation and work is undoing the sense of ‘things happen to me.’ We are here to create a space for growth and learning, but also to help students figure out how to respond to . . . life.”

Kim added that she hates being in the limelight. When she heard she had won the Excellence in Education Award, “I thought surely they could have found someone better . . . but, you know, I am honored, and I will admit that I have one helpful quality. I will do what needs to be done to get from here to there. If a student is willing to work 10 hours on a Saturday, I’m there. Until 4 a.m. to catch up on a class? Sure.

“The work and the everyday successes of Eastside over the last 20 years have truly been a team effort, so being recognized for the combined work of so many individuals is a bit of a surprise,” she said.

She is alone in that reaction; others who know the story of Eastside and her role in it are not the least bit surprised.

Giving students a challenge

East Palo Alto badly needed Eastside; the community had long lacked what is viewed as the foundation of equal opportunity in the United States.

Unlike neighboring Palo Alto, East Palo Alto was never a place of quality education, wealth or opportunity. It sprung up as a predominantly black community in the 1950s when Palo Alto deed restrictions prohibited sales to non-whites.

The only high school there closed in 1976. East Palo Alto lost what in most neighborhoods is a unifying institution. All of its high schoolers were bused to neighboring high schools in more affluent communities. They were routinely assigned to non-college track classes, and they dropped out of high school at a rate of 65 percent. Of those who graduated, less than 10 percent enrolled in four-year colleges. Meanwhile, the drug culture of the 1980s attracted dropouts who were poorly prepared for even blue-collar jobs. East Palo Alto was even left out of the dot-com boom that enriched Silicon Valley in the late 1990s.

Both Kim and Bischof were aware of this inequity while they were undergraduates at Stanford and then teaching candidates in the Stanford Teacher Education Program (STEP). Both worked in schools where students were struggling with poverty and both did community work in East Palo Alto. Upon completing STEP, Bischof worked at an after-school reading and sports program that he established for middle school kids from East Palo Alto. Kim was teaching and coordinating the English Language Development program at Homestead High School, a large comprehensive school in the Fremont Union High School District.

Kim said that Bischof’s continuing struggles to help students successfully navigate high school toward graduation and college resonated with her, and she shared his desire to improve their education and opportunities, as well as his commitment to social justice. She and Bischof wanted to have a much greater impact, and hatched their idea: Kim quit her full-time, salaried job at Homestead and told her parents, “who were not super-excited,” that with some money but no idea where the rest would come from she and Bischof were heading into the unknown to start a school.

Eastside grew slowly, moving to various buildings or trailers in the neighborhood. It eventually drew benefactors who enabled the construction of its current modern campus on Myrtle Street, which was completed in 2007 and includes dorms for about one-third of its students who benefit from a more structured academic environment. The student body reflects its neighborhood — roughly 65 percent Latino, 31 percent African American and 4 percent Pacific Islander. (The demographics of East Palo have shifted from African American to Latino over the last 50 years.) Every student is on full academic scholarships provided primarily by gifts from individuals as well as grants from foundations and corporations.

Kim delights in noting community events that take place at the school, such as a recent graduation ceremony in the school’s theater for the East Palo Alto police force. The school is also a training ground for student teachers from Stanford.

Eastside is known for its rigorous curriculum, layers of support for students and their families and an ethos of “we can always do better.”

Kim believes it is the school’s job “to challenge students more, create richer opportunities, better meet individual needs, and adjust the curriculum and instruction in response to the changing world of work and study.”

Such dedication is convincing many Eastside graduates to enter the profession. Marissa McGee, for example, graduated from Eastside in 2004, went onto Stanford and STEP, and now teaches underprivileged students in the District of Columbia public school system and stays in touch with Kim.

“Her commitment to her current and former students is genuine, personal and long-lasting,” McGee ’08, MA ’09 wrote for the document nominating Kim. “I hope to have similar impact on my students.”

Seduced by teaching

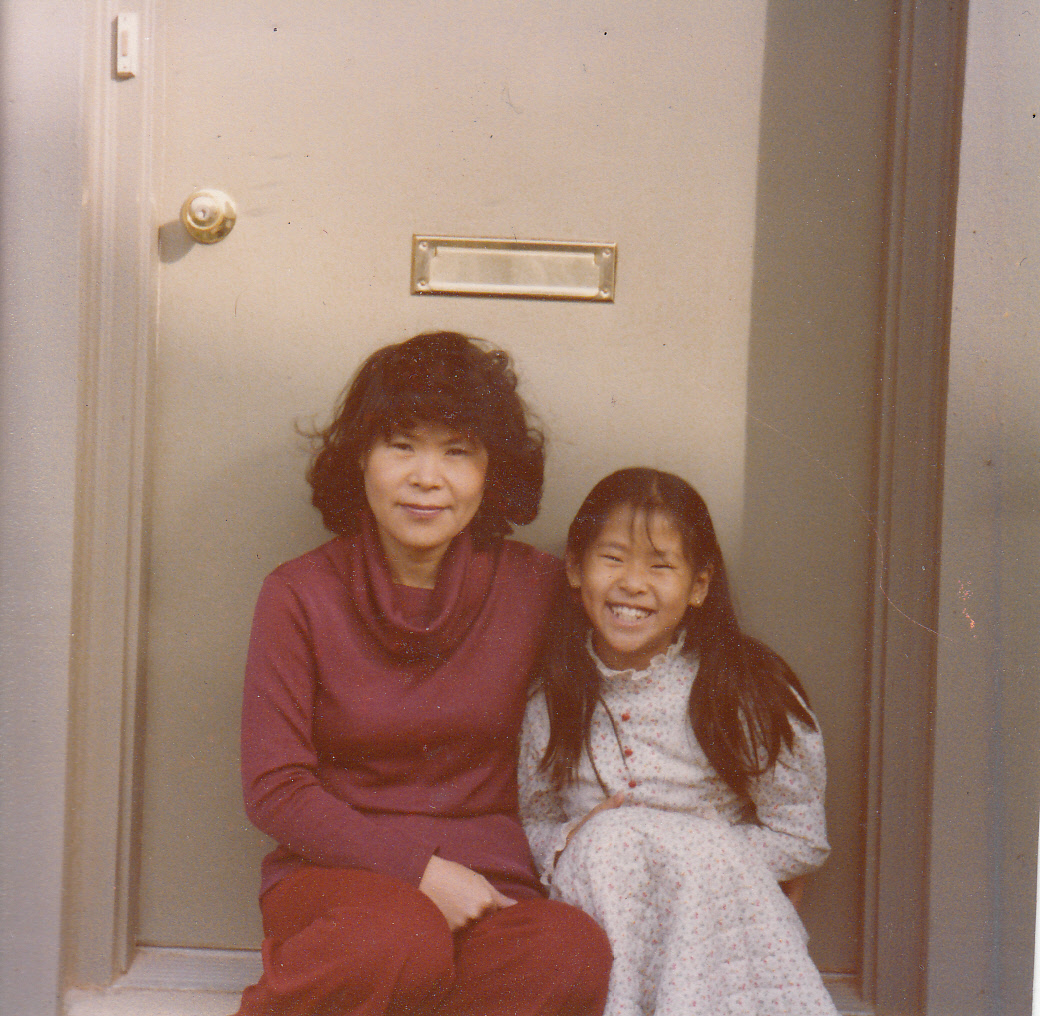

Kim is the second of two children of Korean immigrants who arrived in Maryland when she was 5 years old. Her father, Young, is a Baptist minister and her mother, Kay, worked in the field of computer-aided drafting. Her brother, Samuel Kim, graduated from Stanford in 1989 and is an attorney.

Kim described her mother and father as “first-generation” parents who worked hard to benefit their children’s futures and whose senses of generosity and social justice made a deep impression.

And, as a pastor, “my father was always the person people called upon for their needs, so I learned to be incredibly patient waiting for him to finish advising and helping people after church,” she recalled.

Kim left Maryland for Stanford and has been a Californian ever since. She started college on the pre-med track, taking calculus and the chemistry series in freshman year. Those plans changed after a stint working as a clearinghouse peer advisor at the Haas Center for Public Service. As such, she visited many public service organizations. She also worked with the Consortium for Young Women in East Palo Alto and then received a summer fellowship grant from Stanford to run a summer program for middle school girls in East Palo Alto.

Hooked on education, she worked with (the late) Elizabeth Cohen, professor of education and of sociology, for her undergraduate honors thesis in education during her senior year at Stanford. Cohen was founding director of the Program for Complex Instruction, which applies sociological theory to promote racial, ethnic and gender equity in classrooms.

Despite all that, Kim took the LSATs just in case she decided to be a lawyer. “I was not convinced that teaching would be what I’d be good at,” she said. “As a fairly introverted person, the idea of teaching as a profession didn’t seem like a natural fit. As a person who likes to learn, do better and make things better for others, it turned out to be a pretty good fit.”

She said the Stanford GSE and real-life teaching seduced her, heart and soul.

“In addition to the opportunity to read, think and discuss, my graduate school experience connected me to a community of educators who pushed me to clarify my own thinking about education and my priorities as a teacher. My biggest takeaway from the GSE has been its culture of thoughtful, continual reflection on teaching practice. Teaching is complex and demanding. To do it well, it is also really difficult. Having the mindset of continual improvement based on analysis of student learning and changing needs is critical,” Kim said.

“Like the trajectory of growth and learning that our students experience over the course of their middle school and high school years, it is amazing how much we learn as teachers in the course of the same time period. You get better, more thoughtful, more confident and more humble with each new year,” she said.

Curriculum, discipline, staff development and a delivery of bananas

Colleagues and friends say that the definition of “humble” and “dedicated” could be listed in a dictionary as “Helen Kim.”

Kim often turns questions about herself and her role at the school toward praise of her colleagues, students, the campus and the school’s benefactors and Bischof. While Bischof and Kim collaborate closely, he focuses more of his time on raising the support needed to run the school and is the public face of Eastside. She described herself as more the daily mechanic – even though, she said, Bischof is just as good as she is at the things she does.

“That’s her!” said Rachel Lotan, director of STEP and a member of the award selection committee. “She is so humble. The school is such a happy place, and that is a tribute to her. ”

Tales of Kim’s work ethic and dedication stand out even in an atmosphere of extraordinary commitment by students, faculty and parents. Reilly described her daily schedule as “dizzying” because there “is no limit to the extent she will go to help people.”

On a recent afternoon, Kim juggled paperwork in her small office decorated with a couch, piles of books, papers and construction-paper mementoes from students before she ventured into the school’s lobby. There, within just five minutes, she discussed with 11th-grade English teacher Sarah Kreiner ’08, MA 09, the process that would be taken to acquire a substitute teacher for Kreiner’s maternity leave; wrote late slips for a group of teen boys; advised Vonisha Raines, 17, about the senior fundraiser she was managing; escorted a recruiter from Dartmouth College to meet seniors who were considering the Ivy League school; signed for a FedEx shipment; greeted a grandparent delivering bananas for his granddaughter who lives in the school’s dormitory; and calmed a student who did not want to have her class picture taken after a sweaty gym class.

Aside from managing the faculty of 36 and guiding the curriculum, Kim tutors; substitute teaches and is the lead contact for the school’s accreditation process. She is the coordinator of all College Board tests and the point person for class trips.

She handles scheduling, discipline, staff development and big-picture curriculum design. She led the charge to increase Advanced Placement offerings on campus and supervises student activities and late-night homework. She has visited students and alumni who are hospitalized and has played board games with their worried families in waiting rooms.

Kim is single, an inveterate reader, loves to travel, recently bought a home in Menlo Park and, in addition to the issues of education and equity, is concerned with wildlife and habitat conservation.

“But the most fun thing for me is when, at the end of the day teachers send students to my office, where I have a mini-library and they sprawl on my couch and we talk about books,” she said.

Asked what else she enjoys, she answered, “All this,” and held out her arms as if she were embracing the school. “It has been my life’s blessing,” she said. “More than anything, I am grateful to be able to do the work I get to do every day.”

Joyce Gemperlein, a freelance writer in the Bay Area and a former Knight Fellow at Stanford, is a contributor to the Educator, the online newsletter of Stanford Graduate School of Education. Please read our previous issues and subscribe.

All photos courtesy of Helen Kim and Eastside College Preparatory School except where otherwise noted.