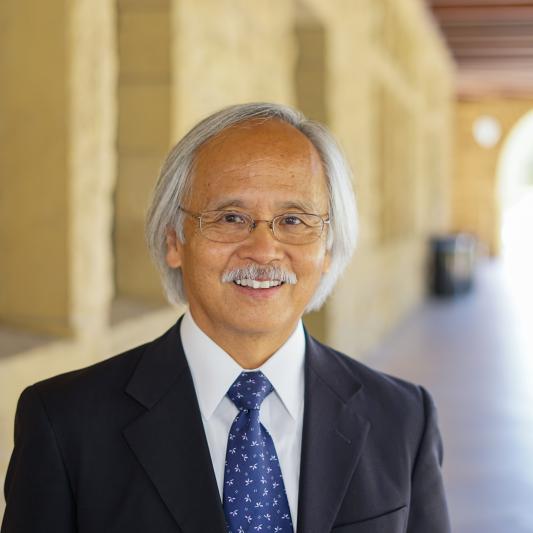

Gary Mukai, MA ’81

Gary Mukai, MA ’81, enriches classrooms in America and beyond as head of the Stanford Program on International and Cross-Cultural Education

Globalizing K-12 curriculum for a diverse world

Gary Mukai, MA ’81, enriches classrooms in America and beyond as head of the Stanford Program on International and Cross-Cultural Education

By Barbara Wilcox

Students from New York to San Francisco know the importance of the Silk Road and pathways like it in transmitting technology and culture. Students on the Pacific Rim understand their region’s interconnectedness – whether they live in California or in China, Korea or Japan. Teachers in all these places better understand their students’ heritages.

All are helped in this understanding by Gary Mukai, MA ’81 (SIDEC), who provides multidisciplinary curriculum and teacher development to millions as director of SPICE, the Freeman Spogli Institute’s Stanford Program on International and Cross-Cultural Education.

For his energy, humility and commitment to globalizing K-12 learning, Mukai is honored in 2017 with the Stanford Graduate School of Education’s Alumni Excellence in Education Award.

“It is his inner passion and unwavering determination to create high-quality education tools for children around the world that makes him an inspiring leader,” said TeachAIDS CEO Piya Sorcar, MA ’06, PhD ’09, a prior honoree who nominated him for the award.

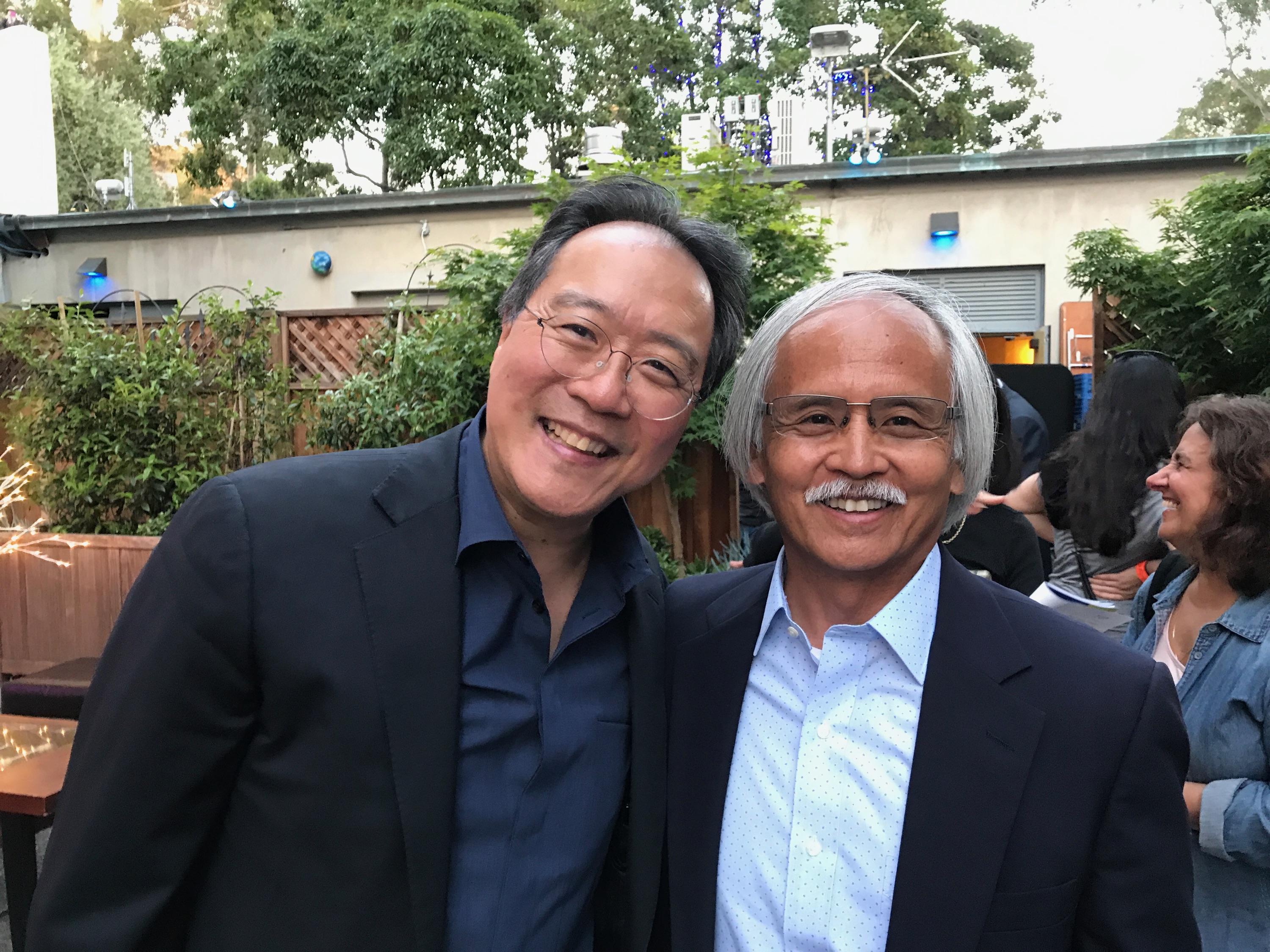

SPICE has partnered with cellist Yo-Yo Ma’s Silkroad project, including Syrian clarinetist Kinan Azmeh, to reveal how the arts can build bridges in times of conflict. It has built curricula around the Beijing Olympics; the role of indigo in world trade; and arts and religions of the historical Silk Road.

“It’s sort of a soft-power approach to building better international relationships,” Mukai said.

Mukai grew up in south San Jose in the 1950s and ’60s, when it was still agricultural and rural. His neighbors were braceros, Mexican immigrants who entered the United States under a federal program to ease farm-labor shortages during World War II.

“I grew up feeling more Mexican than Japanese, which helped influence my career direction and had a profound effect on my thinking,” he said.

Entering UC Berkeley in 1972, Mukai happened onto a course by ethnic studies pioneer Ronald Takaki, famed for introducing what were then relatively unstudied perspectives on U.S. history, including those of the braceros and of Japanese-Americans interned during World War II.

“It was the first time in my life that a teacher seemed to place importance on knowing these things,” Mukai said. “Things I already knew from my own and my family’s experience.

“But hearing about them in the classroom was a different lens through which to critically think about them. It really shaped my desire to become a teacher.”

In 1980 Mukai entered the Stanford International Development Education Center (SIDEC), the precursor to today’s GSE program in International Comparative Education. Though he was interested in curriculum, Mukai chose SIDEC over a program in curriculum “because I got to hear diverse perspectives from around the world.

“One thing that attracted me to SIDEC was the fact that we were required to take courses with Prof. Martin Carnoy. He focused on education and economics. Prof. Joel Samoff, an Africa specialist, introduced us to the politics of education. Edmundo Fuenzalida, then a visiting scholar from Chile, taught the sociology of education.

“Meanwhile, I had a chance to attend brown bags and talks with people like Prof. Lee Shulman. Even though they weren’t part of my curriculum at SIDEC, they had a profound effect on the shaping of my career. I still draw on all their work today.”

Mukai noticed that classmates from different countries and circumstances brought different perspectives to the material, and that this difference was itself a source of learning. He carried that value of exploring and learning from difference into his professional life.

“In Martin’s class, I remember reading a book on dependency theory by Fernando Henrique Cardoso, who later became president of Brazil. He introduced this idea of the periphery and the core, with the U.S. and Europe as the core, the periphery being ‘the Third World,’ as it was called then.

“Those things were really new to me. They weren’t at all new to my classmates from Latin America. Their perspectives stay with me still to this day. It’s fascinating to think about what I learned from them.”

He taught in Mountain View public schools before joining SPICE and reconnecting with his former mentor, Prof. David Grossman, SPICE’s founding director. SPICE’s roots date from 1973, when a program linked Stanford content experts with Bay Area teachers eager for China material in the wake of Richard Nixon’s epochal visit. Three years later, SPICE was formed with global scope. Its mission has broadened, both in content and pedagogical strategy, as content standards change and immigrant populations diversify.

“In California, we’ve for a long time had minimal coverage on, for example, Chinese and the railroads, or the Gold Rush,” Mukai said. “Now textbooks address these in greater depth, and add more experiences. Why are Vietnamese in the United States? We address the fall of Saigon. The 2003 centennial of Korean immigration to the U.S. led groups within the Korean-American community to call for opportunities to make it educative.”

SPICE seminars for teachers address not only content, but also the diversity of immigrant populations and how student performance may be affected by different education systems or traumatic experiences in their countries of origin.

“Participating in SIDEC created disequilibrium in my educational life,” Mukai said. “So many things were very new to me that I had never thought of before. The SIDEC scholars challenged my assumptions.

“I remember that feeling of disequilibrium, whenever I’ve had it. It can be a powerful moment for change and understanding. So much of that continues to stay with me.”

Learn more about the Stanford Program on International and Cross-Cultural Education (SPICE) and its resources for teachers and students.

Watch video about SPICE’s free teacher-development seminars about east Asia.

Learn about SPICE’s Reischauer Scholars online program on Japan for U.S. high school students.

All photos are courtesy of Gary Mukai.

For more information about the GSE Alumni Excellence in Education Award reception, and to register for this special event, please visit the GSE’s Reunion Webpage.