History

Since the School’s founding in 1917, its faculty, students and alumni have worked to solve education’s greatest challenges and improve lives through learning, discovery and driving change in practice and policy.

The emerging academic field of education was one of the founding departments of Jane and Leland Stanford’s new university, opened in 1891 to foster “direct usefulness and personal success” for the betterment of humankind.

At the time, fewer than 6 percent of Americans attended high school – often because there was no school nearby. Fewer than 2 percent went to college.

Stanford students flocked to the university’s education classes in search of a trade and to help make the schooling that they prized more accessible to all people.

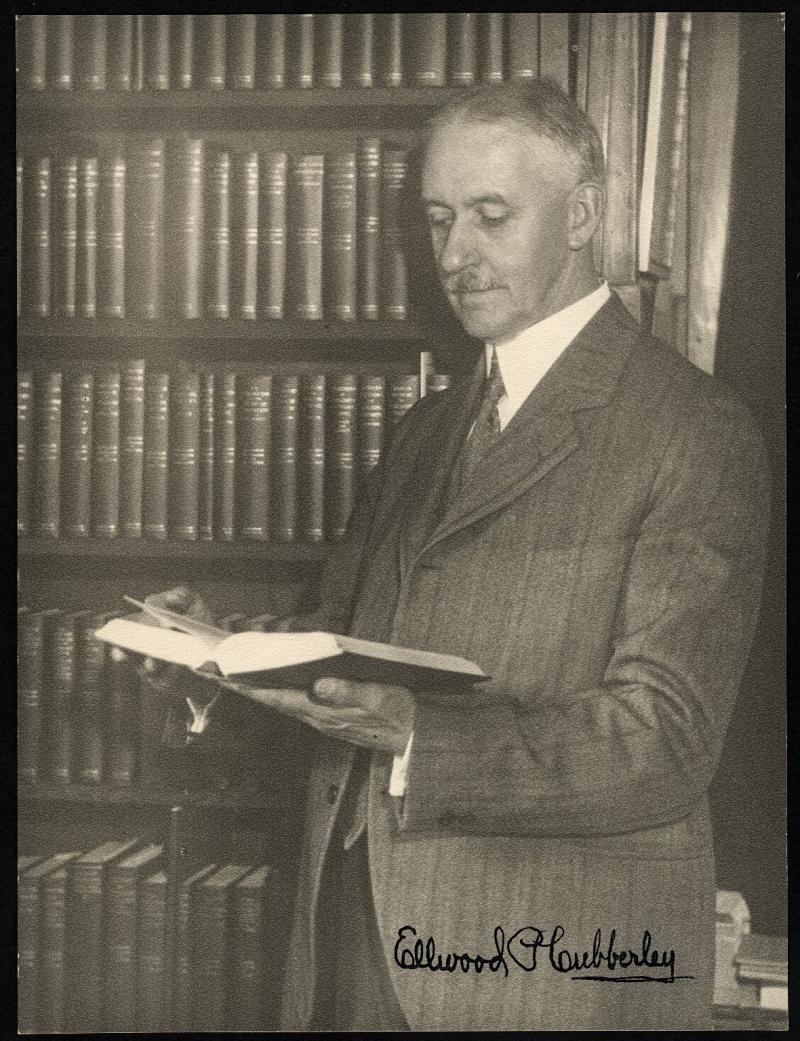

Stanford University Archives

Ellwood Patterson Cubberley, chair of the department from 1898 and founding dean of the Stanford School of Education from 1917 to 1933, found himself not only leading a department and school but helping to shape an entire discipline.

Today, Stanford’s Graduate School of Education carries forward the mission of leadership in research, theory and practice. It uncovers new knowledge of how people teach and learn. It yields teachers, leaders, scholars, founders, policy makers, activists, heads of state. In ways unforeseen by past generations, it furthers Stanford’s goals of improving life for all.

The early years

The son of a pharmacist, Cubberley loved science and grew up mixing chemicals in the family store. He brought to his department a call for data-driven research, for an emphasis on training leaders, and for better materials for all education students.

Developing the field of school organization, Cubberley studied ways to finance, plan and manage efficient public schools at district and statewide scale.

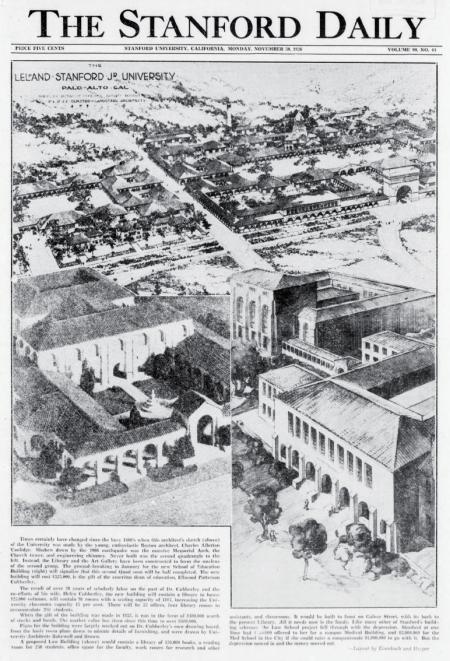

The Stanford Daily

He wrote and edited a textbook series, the Riverside Series in Education, that sold more than 3 million copies. He invested the proceeds, and on his retirement in 1933 in the depths of the Depression, he gave the university more than $375,000 for a School of Education building and for the Cubberley Lecture series that continues to bring world leaders in education to Stanford.

One of Cubberley’s first hires, educational psychologist Lewis Terman, revised a French intelligence test for U.S. audiences. Terman’s Stanford-Binet test, unveiled in 1916, purported to measure innate mental capacity in a succinct and easily administered form. In an era that prized efficiency, the Stanford-Binet brought Terman – and Stanford – worldwide fame. The pitfalls of this approach to allocating social and educational resources took decades to explore and acknowledge.

Global shift

During World War II, Professor Paul Hanna helped Stanford prosper by negotiating lucrative training contracts with the federal government. This work exposed Hanna and his colleagues to international issues, notably the potential of education to further global understanding and development. It helped shift the school’s outlook toward the wider world.

Grayson Kefauver, Cubberley’s successor, helped create UNESCO, the United Nations Educational, Social and Cultural Organization. Kefauver was UNESCO’s chief U.S. delegate when he died suddenly in 1946 at the age of 45.

Deans I. James Quillen and H. Thomas James raised the school’s reputation by hiring top social scientists in line with postwar university President Wallace Sterling’s aim to lift Stanford into the top ranks of U.S. research universities.

They strategized laboratories for school planning, child development, the Center for Research and Development in Teaching and today’s CERAS (Center for Research and Education at Stanford), opened in 1972. Doctoral training increased in priority and scope.

Meanwhile, the school forged research-driven ways to enhance teacher training. In 1959, it founded the still-popular Stanford Teacher Education Program (STEP) to blend research and practice by forging experimental methods of teacher preparation.

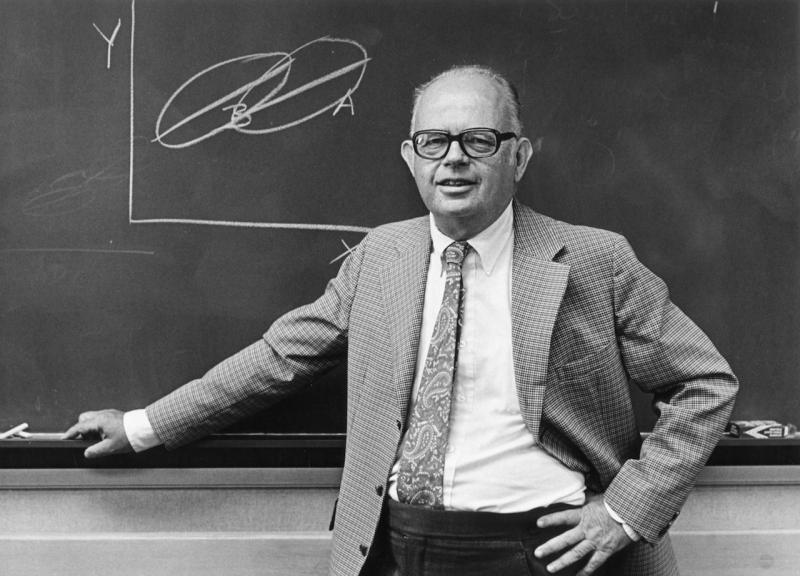

Stanford News Service

Chuck Painter/Stanford News Service

Diversity, equity and policy

In the late 1960s and early 1970s, the School of Education’s efforts to diversify its faculty, its student body and its concepts of equity and access reverberated across the university. The first Chicano hired as a full professor at Stanford, Alfredo Castañeda, was tenured in the School of Education in 1972. Labor economist Myra Strober, founder of Stanford’s Center of Research on Women, was tenured in the School of Education in 1973.

Christopher Wesselman

Concern nationwide in the early 1980s over public schools helped refocus attention on classroom practice.

Michael Kirst, who helped craft the Title I program for low-income students as part of Lyndon Johnson’s Great Society, was hired as part of the school’s emerging goal of shaping education policy. Later, practitioners and activists were inspired by Linda Darling-Hammond’s arguments for educational equity and policy reform.

Judy Avery, ’59, helped lift bars to a teaching career by underwriting a student loan-forgiveness program for STEP students who go on to work in public or under-resourced private schools. Other programs, including the full-tuition STEP Teaching Fellowships, now help democratize access to Stanford for future teachers.

A unique partnership forged in 2009 by leaders at Stanford, the San Francisco Unified School District and California Education Partners improves the links between research and practice in San Francisco's public schools.

The partnership matches researchers from Stanford with district leaders to solve key problems of practice, and serves as a model for others.

Learning for all

In 2013, the school rechristened itself the Stanford Graduate School of Education in line with its historic emphasis on advanced study and the shaping of leaders in policy, research and practice.

Today, the school maintains 16 research centers in concentrations ranging from cognitive science to community youth development. It offers 21 doctoral programs in policy studies, developmental and psychological sciences, learning sciences and technology design, and curriculum studies and teacher education; seven master’s programs; and an undergraduate minor and honors program.

In 2015, cognitive psychologist Dan Schwartz was named dean of the school. Schwartz's research focuses on how people learn. His AAA lab develops teaching and learning technologies and supports research that informs processes of learning, instruction, assessment and problem-solving.

Under Schwartz's leadership, the school is investing more deeply in scholarship on the needs of learners in peril - those students who need high-quality education the most but have the least access to it.

It formalized a cross-disciplinary program in 2017 called RILE (Race, Inequality and Language in Education), building a stronger community of scholars focused on these fields.

The school is also working to ensure the success of future learners and teachers by anticipating the great game-changers in education and by discerning where research can have the most impact. These fields include technology, data and brain sciences.

Linda A. Cicero/Stanford News Service